When you work as a registrar you often take for granted that you know what other registrars in other museums do. But when you talk to colleagues from different museum types you often realize that some things are similar and other things are very different. When Fernando told us he was preparing an article on the registration of contemporary art, we accepted the challenge to write one on the registration of technological objects. So, if you are into the arts: let us unfold to you the wonderland of technology. If you are into technology: Look over our shoulders and tell us if we forgot something important.

Registering technological objects: a look on the surface

When registering a classical artwork, you normally know the artist and the date of the artwork. You can measure the dimensions and register the technology used in the classical way: oil on canvas, watercolor, lithography… Most of these things can be easily seen with one’s eye, given you have the proper knowledge and training in art history and techniques used by artists – and the whole process of accessioning has gone right. Granted, when something went wrong and you don’t know who painted the artwork, things can become tricky. Then you have to get your registrar’s and art historian’s senses together and start to investigate.

When registering technological objects, that’s just the beginning. Let’s take a simple ancient radio. It has a manufacturer and if you are lucky it is written on the device. It might also come with a type label that provides additional information. If you are very lucky, this label shows the year of construction. But that’s not often the case. So you go and look for old radio catalogs and try to find this type of radio. If you have a good library of ancient mail order catalogs and catalogs for radio retailers you have a good chance to find the year, or more likely years of construction.

If you have no manufacturer and no type label, which isn’t uncommon, the catalogs are also a great place to start your research. Of course, you should have a certain idea from which time span a radio is, otherwise you will have to dig through decades of catalogs. That’s where the art sphere comes in. You can vaguely estimate the years of construction by looking at the design of a radio. But this can fool you, too. For example:

Manufacturer BRAUN developed an incredible clear and functional design, inspired by the Bauhaus movement and in parts developed by professors and students of the famous Ulm School of Design as early as 1955. If you look at certain radios from this period, you would swear they were made deep in the 1960’s. At the same time manufacturers like Grundig produced radios that look a bit like neo-baroque (although, if you take a look at Braun’s SK61 http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Braun-Sk61.jpg and Grundig’s SO271 http://www.radiomuseum.org/r/grundig_so271_barock.html both built in 1961 it’s hard to stay neutral and to suppress the urge to tag the latter under „monstrosity“).

So, what do you enter in the data base? In the first place you enter the manufacturer and then, in some rare case, where you can figure it out, the designer. A little upside down situation to the arts world, where it’s common that you have the artist in the first place and only in some cases an additional manufacturer, most commonly a printer.

Staying with the dates: for our design approach can lead us off the track, it’s safer to stay with technology. It gives us great hints to stay in the right era. Some manufacturing techniques are labor-intensive, and therefore point us to early decades: riveting is more labor-intensive than spot-welding, for example. In times of war, economy of scarcity rules and you will realize that on the used materials: a necessity to use materials you don’t have to import and to use as little as possible of them. Speaking of materials, they also give clues for the date: synthetic materials were developed through the last hundred years and are still improved. So were production processes that you can trace on the object: injection molding will leave marks of the ejector on the formed parts, for example. So, the knowledge of materials and technology will help you a great deal in dating the object.

Next, you want to find out where the radio is made. That will be another research. You will most certainly find the place where the manufacturer has his head office but that’s not necessarily the same place he manufactures the radios. Big companies tend to have production places throughout the nation, if not throughout the world. Some might even produce the same radio in different plants. Some might cooperate with other manufacturers so the radio is built in the plant of one manufacturer but has the name of a second manufacturer on it. Much to register…

Easy going: the dimensions

To reach safe ground again we measure the radio. That’s simple. Height, length, depth. But wait! What’s about the cable? It sticks out of the silhouette. If we just measure the dimensions of the box, every showcase maker will be in trouble, because he didn’t know he has to add space for placing the cable. If we measure the maximal dimension with the cable in every direction, we will get ridiculous vast dimensions. If we just fold the cable behind the box and add the measurement to the measurement of depth? Well… someone might re-measure just the box, coming to the conclusion that this can’t be the radio he searches for, because the data differs.

Best solution to this issue – that drove generations of exhibit designers crazy – is to add an information to every measurement. For example: „box“, „cable length“, „measured when closed“ or „with lids open“.

Technical data: A look inside

What about the technical data? In the field of classical arts you can keep it simple and to the point most of the time. „Oil on canvas“ for example includes every technical information you need. You know what to expect, even without seeing the actual picture. As an experienced registrar you can even give a complete catalog of required storage conditions without actually thinking about it.

What is the technical data of an ancient radio? The materials used are wood, metal, glass and most certainly plastics. It might have a textile cover over the loudspeakers, too. And that’s just the outside. When you remove the back board you will find tubes, resistors, capacitors, inductors and cables. So the material list is enhanced with paper, lead, tar, wax, glue and certain kinds of synthetic materials you prefer not to think about too deep (Phenol formaldehyde resin, for example). The capacitors are filled with electrolyte, so you have to deal with liquids as well.

What are the ideal storage conditions for this material mix? Well, the one thing I can tell you is that there are no ideal storage conditions for this. You can just try to keep the climate stable but you will certainly knock off some bars for some materials.

And what about the techniques used? Well, wood will be sawed and joined, glass will be blown, metal can be pierced, bent, rolled, pressed, welded, spot-welded, riveted, soldered, screwed,… Are you still with me?

So, if you are detail-orientated like most registrars are, you will find many, many things to register. Take into account that each component like an electronic tube has its own manufacturer and year of construction, has its own purpose like amplifier tube or rectifier tube and technical data like voltage and power that separates it from the other components that might look similar at first glance. And this is just a simple radio. You don’t have moving parts like little electric motors and drive belts you will find in a tape recorder. And it’s far, far away from the things a car consists of.

Beyond technical data: the context

Human beings use technology to shape their environment. And vice versa technology shapes human beings. Don’t believe us? Just take a look at people waiting at a bus stop today and try to remember how it was ten years ago. While then they were reading newspapers or books or were staring as life went by, nowadays most people stare at their smartphone. So technology shapes our behavior and this is a fact since the first human discovered that he or she could use a stone as a tool.

Coming back to our radio, the use of this device changed people’s lives. Before its invention, you got news from the newspapers, about a day after they happened. With the invention of radio broadcasts you had the news only a few minutes or hours after they occurred. When radio came up, it was a sensation. There were only few broadcasts, not the 24/7 broadcasts we are used to today. When something was broadcasted, often the whole family would gather around the radio to listen – in the early days every family member with a headphone.

Young child listening to a radio, 1920-1930 (Item is held by John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.)

Manufactured radios were scarce and expensive, so many people started to build radios themselves. It was a tremendous do-it-yourself movement. Manufacturing developed soon and in the 1920’s German manufacturers developed plans to build an affordable radio by sharing costs through standardization. It is often believed that the “Volksempfänger” VE 301 was a development pushed by Hitler, but in fact the plans reach back much further.

After the war the use and role of radio changed. Efforts were made to make the radio a portable device which could be done effectively after the invention of the transistor. When TV came up, it pushed aside radio as the place the family would gather around in the evenings. Listening to the radio became an activity done alongside another, more important activity like cooking, ironing or driving a car. That’s where radio is until now – well, not quite. With internet radio humanity has broken up the limitations of just being able to listen to radio stations within the reach of the own antenna. It was possible to listen to radio stations around the world through short wave even in the earliest radio times, but then it was still necessary to understand the technology involved. The right device, the right length and shape of antenna, propagation conditions… Nowadays you just turn on your little WLAN radio device and flip through a station list that allows you to listen to a country station in the Middle-West, a samba or bossa nova station in Brazil or some traditional music in Mongolia. You don’t need to know how it works, you just need to know how to handle your device (given, some menus are so complicated to understand that you just wish they were as easy and logical as the calculation of a dipole antenna).

How does this help in the registration of our radio? Well, if you have the development history in mind, it’s easier to track down and understand signs you find on the radio.

You might be able to trace the story of a common household appliance: while it might have been the center of family live in the beginning, layers of grease mixed with dust can indicate that it was the kitchen radio after a new and better model or a TV set came to the family. Signs of seams of glasses can indicate it was used frequently to put the drinking glass down, telling you it had a place in the household where one was tempted to do so, maybe the bedroom of a teenager? You might find someone decided to wrap it with self-adherent design foil to give it a fresher outfit in the 1970’s. Or, to the opposite, grounded off the original varnish and painted it over white to make it fit in the modern living room. You might find signs of restoration from the time the model gained collector’s value. Or maybe it is in an incredible good shape, looking just like it came from the plant, because it was held in high esteem over the years.

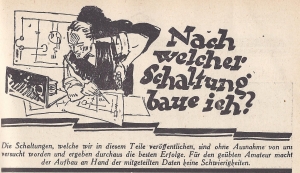

Self-made radios were common in the ealy days of radio, so was the knowledge of the technology involved. Header of the category “Which wiring do I chose to build?” of the popular German monthly journal “Radio Amateur” (taken from the issue 12/1928)

If you open the backside you might find alterations to the original wiring scheme, done to listen to frequencies originally not intended to be received with that radio. Maybe just because the original owner wanted to receive another allowed frequency, but maybe because he wanted to listen to “forbidden” stations (foreign broadcasts in wartime, for example). You might also find alterations done to insert a different type of tube, because the original one was no longer available or others were cheaper.

It is your responsibility as a registrar to be able to read the signs but also to act as a good investigator. Assumptions have to be marked as such. They can be verified by asking the donor about what he or she can remember about the object. If you are lucky, the radio came with documents: the original invoice, the license to use it or a photo of the proud owner. These documents have to be properly filed and referenced in the data base. If you get additional hints and stories from the donor, they have to be documented as well.

The radio is a part of human history. Maybe a small part but as we are keepers of the cultural heritage we are responsible to keep important information together.

How deep is your registering?

Having read so far you surely feel overwhelmed by information and possible things to register. They all seem important, adding context and meaning to this special object as well as to the history of radios in general. Your observations on this object might indeed be helpful to verify or falsify theories of historians.

The perfect way to store technological objects? Certainly not! But it’s still how some people think it is in the storage of a science and technology museum… (picture: Philip (flip) Kromer from Austin, TX)

But in reality we don’t have as much time to invest in a single object. We have to make decisions on what to register and what not. Especially, as we registrars in science and technology museums are often carrying a burden from the past: For years, the custom in collecting technical objects was similar to how you run a junk yard: You just collect them and pile them in large industrial halls without documentation. Heck, they are just industrial mass products; you can document them sometime in the future, right? Well, we all know that this was not right, that we lost information because of the carelessness of our ancestors. So part of our work is to research and to give the objects in our collections their history back.

So, we have to limit ourselves in the registering of the single object to get more done in the whole collection. Sometime in the future we will write something about how to conduct a “triage” to protect and document as many objects as possible as primary care.

TV storage gone wrong? Nope, we are back in the arts sphere: That’s “Sensory Overload” by Nam Jun Paik (picture: Arti Sandhu)

How deep we go with registering an object is a decision on a by-case basis. For most exhibitions or loans a documentation of basic technical data that can be measured and can be found on a type label is sufficient, along with a rough estimate of the manufacturing time. There are specialized research and exhibition projects that need a more thorough documentation. But then again, that’s where you can use synergistic effects. These projects can have specialized curators and scientists that provide additional data. Or the projects are funded in a way that you can invest more time on detailed registration.

In a way, registering technological objects is squaring the circle: When you register most accurate, you can’t register many objects. If you register not accurate enough you might reach high numbers but produce data base entries that are all but helpful. While “The Night Watch, Rembrandt van Rijn, 1642, oil on canvas” says sufficiently enough, “Radio, BRAUN, 1950-1959, wood” says nearly nothing. So, it’s up to the registrar to find a good middle ground between being too detail-oriented and being too common.

Angela Kipp, Bernd Kießling

__________________________

Bernd Kießling holds the job title of “Museologe” at the TECHNOSEUM, Landesmuseum für Technik und Arbeit in Mannheim, Germany. His working area can be compared to the work of a registrar. His areas of expertise are the collections of radio, television, radiocommunication, computer technology, office technology, photography and nuclear technology.

This text is also available in Italian translated by Silvia Telmon.

So we bring all this into the house and lug it up those oh-so-narrow stairs with that railing that is specially designed to catch and hold vacuum-cleaner hoses, and we put everything down. The only trouble is, there isn’t any place to put it down. Except the floor or the windowsills. Can’t put your dusting brush on the dresser, can’t lay your vacuum attachments on the trunk, can’t sit on any of the chairs when you get tired. Ever tried putting together a vacuum cleaner while wearing gloves? Ever tried vacuuming in a house that has exactly two outlets? Ever tried vacuuming in a house where you can’t touch the furniture with any part of the vacuum or with your bare hands? Where you have to vacuum with the grain of the floorboards instead of across? Where, to get behind or under a large piece of furniture, you have to have two people wearing gloves lift it up to move it so you don’t scar the floorboards?

So we bring all this into the house and lug it up those oh-so-narrow stairs with that railing that is specially designed to catch and hold vacuum-cleaner hoses, and we put everything down. The only trouble is, there isn’t any place to put it down. Except the floor or the windowsills. Can’t put your dusting brush on the dresser, can’t lay your vacuum attachments on the trunk, can’t sit on any of the chairs when you get tired. Ever tried putting together a vacuum cleaner while wearing gloves? Ever tried vacuuming in a house that has exactly two outlets? Ever tried vacuuming in a house where you can’t touch the furniture with any part of the vacuum or with your bare hands? Where you have to vacuum with the grain of the floorboards instead of across? Where, to get behind or under a large piece of furniture, you have to have two people wearing gloves lift it up to move it so you don’t scar the floorboards?