It might sound trivial at first that a beetle isn’t a household article but if you look closer, it isn’t. When a coffee cup breaks during a move you just go ahead and buy a new one. It gets annoying if it belonged to a set that went out of production a while ago. It becomes an irreplaceable loss if said coffee cup was connected to a special memory, for example because it belonged to your great-grandmother or because your child made it themselves.

Museum collections are pretty similar to the last case but now it isn’t just about the memory of one person or a family but about the history of humankind. Which means that the loss is far more grave.

Now, when it comes to collections of natural history an additional aspect comes into play: here, the loss of one object equals an irreplaceable loss of information that is important for current and future research. This is of course also true for art and history collections but in these cases at least the loss can be tempered if the object was well documented and digitized. Our beetle, on the other hand, is a repository in itself. Only this one specimen was collected at precisely that time and precisely that place and preserves all information about its environment at that time. No form of documentation and digitization can anticipate all the questions future generations of researchers will have. The preservation of that information is only possible by preserving the beetle itself.

Not all beetles belong in a collection

Because the preservation of the objects is so important generations of researchers tried to keep them out of harm’s way. Now, natural history collections are especially attractive to pests and therefore every biocide the chemical research and industry discovered in the last centuries was used in them. DDT with insect collections, arsenic with taxidermies, mercury in herbaria, from nerve toxins to organophosphates you are handling everything that can harm your health or even kill you.

In case of a collections move this means you have to deal with two aspects absent from a conventional household or office move:

- You have to prevent pests from getting to your objects during transit. This means that the items you are moving need to be packed the way no pests can get inside and that you have airlocks and quarantine stations on your transport routes so you can be sure nothing got infested.

- When planning the work to be done in preparation for the move you have to keep in mind that you are handling toxic goods. In the past the use of biocides was rarely documented and the only way to be sure what you are dealing with is gauging your collection before you actually start working. This will tell you which precautions you have to take previous to packing and moving and what you have to account for in the new storage.

On top of that there is another danger: the objects themselves. Some of them are toxic or radioactive and therefore you have to treat, transport, and store them differently than your common coffee cup.

Packaged beetles – No package tourists

Transports get quickly done if things can be standardized. You know that from moving house: if you can use standard packing crates they will fit seamlessly into the truck. All you have to do is pack them in a save and reasonable way and avoid overloading.

In natural history collections there are many things that can be standardized: Our beetle will most likely be stored with a lot of its fellows in one drawer and this drawer can be neatly packed and moved with other, similar drawers. But a lot of other specimen don’t do their collections managers the same favor.

Many are stored in glass containers filled with alcohol or formaldehyde which means they are not only fragile but also sensitive to vibrations and their contents inflammable and noxious. You are also not allowed to transport them through a water protection area, which you have to account for when planning the shipment routes.

This is but one example of the many special, non-standard cases you have to deal with when planning the move of a natural history collection. Some specimens are so heavy you need to hire specialized riggers to move them. Others are so fragile you need to get special crates built for them. Many are both heavy and fragile. Then others are preserved by freezing them and if you want to move them you have to make sure the cold chain stays uninterrupted. A taxidermized giraffe or the skeleton of a whale can keep a whole team of experts occupied for days just to find the best way to move it.

Storing beetles – Not a case for your local furniture store

If you have read this far you already guessed it: if you want to store a natural history collection then this storage space needs to fulfill a lot of criteria. It has to deter pests, have a stable room climate, needs a good air circulation and has to be equipped with furniture that allows objects to sit in them for centuries without being damaged yet be easily accessible for research.

Different kinds of specimen collections can have very different requirements. High humidity is a problem for most of them because it enables mold and attracts pests but a room being too dry can cause problems as well. Fluctuations in temperature can rupture the skins on taxidermy specimens and cause fossils to break. An insufficient air ventilation might cause a high concentration of toxics in a room and/or introduce mold. Good collections storage provides the appropriate climate for each of its collections. They are built the way that even in case of an emergency that results in failure of all technology a good storage climate can be re-established by conventional means in such a short time that no permanent damage or even loss of objects happens.

Accessibility is part of a safe collections storage. You need to be able to remove one specimen in a way the other objects stored with it stay unharmed. Our beetle in its drawer is a real space saver, here. Other specimens need far more space. For example, it has to be possible to remove a specimen stored in a jar of liquid from its shelf without having to move other containers. This means you can’t fill your shelves to maximum packing density and you need more storage space but for a good collections storage this is inevitable.

For all these problems there are good solutions but they are not available in your local furniture or hardware store. There are experts and manufacturers who have specialized on these topics.

Whatever is planned for your final storage has consequences for your move: If your beetle is right now in a drawer that is contaminated by pesticides or simply doesn’t fit into your new storage furniture this beetle and its comrades have to move to a new clean and fitting drawer before the move. It is rather common that one big collections move means a lot of smaller moves beforehand.

Ask the beetle anytime

When art or history collections move they often put parts of their activities in collections, exhibitions, and research on hold. A natural history collection that is part of an international network of research institutions in most cases can’t afford this comparative luxury.

In effect, this means that the move has to be planned and executed very different from other moves. It isn’t possible to pack whole collections and store them in a compact and largely non-accessible way until the big move takes place. It must be possible to get access to every collection and every specimen at any given time.

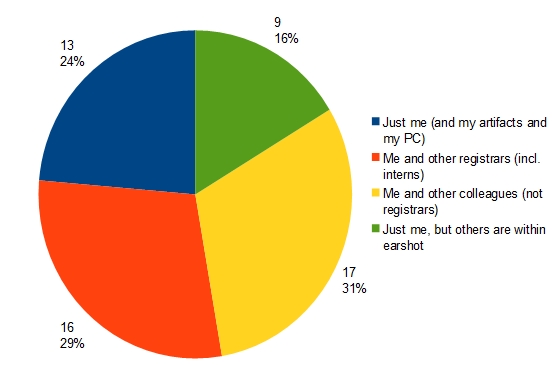

In general, there are two ways of dealing with that: You can limit the time an object is actually crated and in transit, which means that preparation, packing, moving, unpacking, and storing is a matter of just a few days. Or you can crate the specimen in a way that access is possible at any time and without endangering the object itself and the objects packed with it even during the move. Both possibilities have advantages and disadvantages but they both mean that you need more space both in the location you are moving from and in the one you are moving to. It means as well that you need more time and more staff compared to other types of collection moves.

To sum up: Why moving beetles needs a sum of money

With your own experience of moving houses in mind the amount of time, money, and staff it takes to move a museum collection seems to be comparably high. An impression that quickly vanishes when you know the reasons.

Make no mistake, no museum collection is as such “easier” or “harder” to move. Every type has its own, unique challenges. But natural history collections are for sure among the most complex ones you will encounter. And they have a disadvantage: while everybody intuitively understands that you can’t just throw the Mona Lisa on the back of an old truck, a beetle is at first sight “just” a beetle. It isn’t at all obvious that this beetle is a repository that holds perhaps more important and undiscovered information than the well researched and documented artwork by Leonardo da Vinci.

This adds an additional challenge to a move that is already made complex by the variety and sheer masses of objects that have to be brought safely from A to B: the general public has to understand that a beetle is not a coffee cup.

Perhaps this article can help a bit with that.

Angela Kipp