The Next Generation: Breaking Barriers with the Project Registrar Trek

Hyvää päivää. Mitä kuuluu?

Mina olen saksalainen.

Unfortunately, these are the only words I can speak in Suomi, one of the languages in this wonderful country that I had the pleasure to be a guest in for the last few days.

Not more than “Hello, how are you, I’m German.” There is a barrier, a language barrier. Today, I’m speaking about breaking down barriers. Language barriers and other barriers.

Maybe as we sit here together we think that language barriers can be overcome by learning another language. This way we are able to communicate and exchange thoughts, for example in English. While it is true that English enables us to hold conferences like this one, we should keep in mind that we all have just crossed a barrier that leaves other colleagues behind. Who attends this conference? Registrars and collection managers who feel able to follow a conference that is held in English. Others who are not so confident about their language skills stayed at home.

The language barrier might be a problem in understanding each other. But on another level we understand each other very well: we share the language of collections people.

If we talk about lending and borrowing, about storage needs and documentation problems we understand each other, no matter what our mother tongue is and which continent we are from. We understand each other so well that it doesn’t come to mind how difficult it is for other people to understand what we do. This is a barrier not only between us and the visitors in our museums; this is even a barrier between other museum professionals and we, the collections people.

There’s a third barrier. A barrier that is so close to us that we need others to let us see it: it’s the barrier of our everyday work experience, the barrier of our own museum’s walls.

Today, I’m going to introduce a project we started a while ago to work towards breaking these barriers. Some of you might know it already: It’s called Registrar Trek: The Next Generation.

I think there’s no use in clicking through a website and telling you what you see at a conference. That can be better done at home. I think it’s better to tell you something about the general idea of this project, about the spirit of Registrar Trek:

Let us now start to approach the three barriers, starting with the language barrier.

Breaking down the language barrier

The language barrier was the barrier that originally started this project.

We started with three languages: English, Spanish and German. Sure, our translations weren’t always perfect, but it was a start. As soon as we started,

others joined us and right now we have 30 translators from 19 countries providing 16 different languages.

Of course, we don’t have all the posts in all languages right from the start. We are volunteers, mainly working in museums, some studying, some interning, some retired, others job-hunting. So, you can imagine that we are all busy. But because we are many, most of the time we can provide at least 2-3 languages when publishing a new post. Others are added as soon as they arrive.

The good news is that you can’t have too many translators. The more translators we have, the easier it is to balance the workload and the faster we are in adding translations.

So if some of you want to join, I will be glad to say: welcome on board.

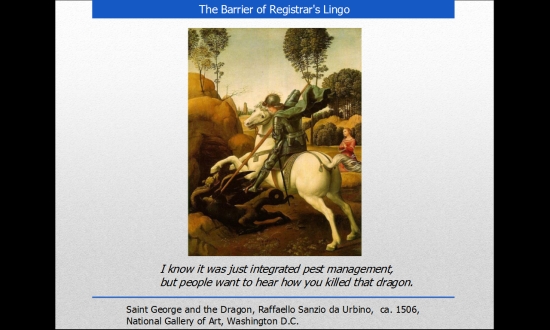

Let’s approach the second barrier: The barrier of registrar’s lingo.

Breaking down the barrier of registrar’s lingo: Telling what we really do

We all know what we do every day. When we talk to each other we don’t have to explain many things. We know what a loan contract is and what a disaster plan looks like, we understand categorizing issues, we feel for a colleague that has to upgrade to a new version of a data base, the list goes on and on.

When we talk to “strangers” about our profession we often realize that it’s extremely hard to explain in a few words what the job of a registrar or collections manager consists of.

The question is: why is it that way? We have such a wonderful, thrilling job, why is it so hard to get the message across? So hard, sometimes even our family members have no idea except that we “work at a museum”?

Personally, I think a big part of the challenge is that we try to explain our jobs in an abstract way.

Let me give you an example: I sit together with colleagues at lunch. The educator tells how he guided a difficult class, the press officer tells how she organized a great speaker for the next event and I say that “I did some integrated pest management”.

While I understand what the educator and the press officer did, they don’t understand what I did.

Why didn’t I break this barrier by saying that I had checked and baited mouse traps the whole morning? Well, that’s not exactly slaying dragons, but in the museum perspective, it’s pretty close.

That’s exactly the approach of Registrar Trek to break this barrier: by telling stories.

I know that „storytelling“ has become a buzzword in the museum field, but the truth is: telling stories is a very ancient way of getting messages across in an entertaining way.

A story about what one has to consider when storing earphones or how one built a box for hundreds of buttons gives a better impression of our job to an outsider than collection policies and job descriptions.

A story about how you climbed the roof of your storage area five times to supervise the craftsmen working there will give a better hands-on impression of the job duties than any handbook.

It will help students and young emerging museum professionals decide if collections is really the perfect fit for them or if it might be better to pursue the marketing or education path.

A story about how you found information about an object that proves its significance for the collection and your community will give other museum professionals like educators and press officers food for their own work and an idea why the work you do is important for the museum.

But telling stories can also help us to approach the third barrier: the barrier of your own museum’s walls.

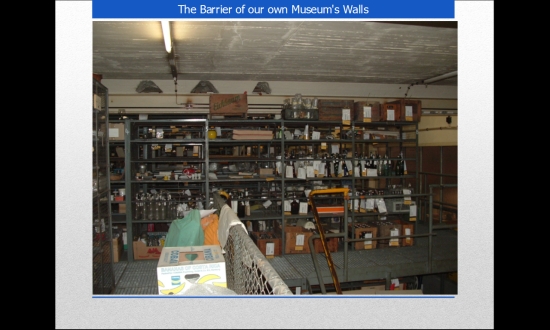

Breaking down the barrier of the own museum’s walls

When you work for a specific museum a long time you become blind to its shortcomings and, more often, you don’t see what works well any more. I brought you a picture:

I don’t know how many of you have had this kind of situation. When you are heading for a museum career you absorb everything about best practices, about good storage conditions, about wearing white gloves. Then you take up a job and start with all the enthusiasm of the young, aspiring museum professional. And then, the real museum world hits you.

In short: you have all the knowledge and the guidelines how it should be but literally no one has prepared you for the situation as it will be.

The trouble is that reading guidelines and official publications of museum associations in such a situation isn’t helpful. Instead it’s depressing. But what might be helpful or at least encouraging is to read stories about how someone brought order to such a mess – or how it could be worse. And if you cleaned out this mess it can feel fabulous to write an article for Registrar Trek about it.

I think our author Anne T. Lane said it best when she said:

“Our triumphs are not like other people’s triumphs. Our crises are not like other people’s crises. It’s good to find ourselves part of a community that understands.”

And maybe, when you publish it, you will suddenly get feedback from colleagues from around the world helping you to see your own situation from a different angle.

When you and I look at the picture the immediate thought is: “What a mess! We have to start cleaning and wrapping those objects, someone go, fetch some archival boxes”

But in a small rural museum in Germany, your colleague (who most certainly will also hold the title of director, visitor guide, administration officer, janitor and webmaster) will say: “Oh, lucky you! You have a room for storage, the roof isn’t leaking and it seems all those objects have labels!”

So, the benefit of writing stories and articles for Registrar Trek is not only to help and encourage others, it can also be a chance of reflecting on our own position. And you create a chance for professional discussion.

Best practices are in constant development and improvement and need creative input that comes out of our everyday, hands-on working practice.

Breaking barriers needs many heads and hands

Right from the start Registrar Trek was meant to be a project designed to involve many people from our profession. It was never about one or two people telling their stories and the others just translating and commenting. (Otherwise I would constantly bore you with stories out of collection management in a German Science and Technology Museum).

We wanted to have collection professionals from around the world bringing in their views, their articles, and their stories. For example, Tracey Berg-Fulton who did the wonderful session before this one wrote an article about how she became a registrar, and that’s just one out of many.

We want you to bring in your views, your articles, and your stories.

The core of Registrar Trek is that it is a common project of colleagues. Standing here alone and telling you about Registrar Trek feels somehow wrong. So, to speak for the authors of Registrar Trek I’m very glad to have Derek Swallow here from the Royal British Columbia Museum in Victoria.

Derek Swallow enters the stage and says the following part:

Thank you Angela.

I want to very briefly touch on two points: how you can contribute if you choose and secondly the rewards of being a Registrar Trek author.

Currently we have four main sections in Registrars Trek any of which you can contribute to: the first is Articles which covers broader issues of common interest and a share point for ideas; next is Stories – this section is comprised of real shared events celebrating learning by way of our successes and failures; the third is called the Registrars Tool Box containing practical solutions, and facts to assist with our day-to-day work; and finally Registrar Humour – I find I need a daily dose of humour to keep me sane in this wonderful but stressful job.

Now the rewards of being a Registrar Trek author: personally, it’s about the process of engaging in communication about museum topics with collections specialists from all over the world. For example, in past articles I’ve presented a new approach to conducting collections committee meetings adopted recently at my museum. I’ve also posed the question: how does authenticity relate to collecting in the 21 century museum? I’ve discussed how our roles as registrars are perceived or misperceived by both the general public and other museum employees.

As a result of writing these articles I’ve received important feedback which has helped evolve and clarify my ideas as a professional in this field as well as establish professional connections with colleagues in Europe, North America and Africa.

I want to leave you with one final thought. In this room 34 nations are represented. If even one person from each nation were to join Registrar Trek as a writer or contributor what an amazing network of communication would open up for us all and can you imagine how broad and rich our exchange of ideas would be?

I thank you all.

Thank you so much, Derek.

I believe we’ve said all we wanted to say about our project. Don’t forget we are always glad to publish your stories. Maybe you haven’t killed a dragon. But maybe you found a great new way of reorganizing your storage space. Or to pack an X-Ray-tube. Or you accidentally loaned 200 artifacts and want to tell others how to avoid this.

Keep up the good work, thanks for listening and may the road rise to meet you.

Kiitos paljon, Helsinki!

This post is also available in Italian, translated by Marzia Loddo.