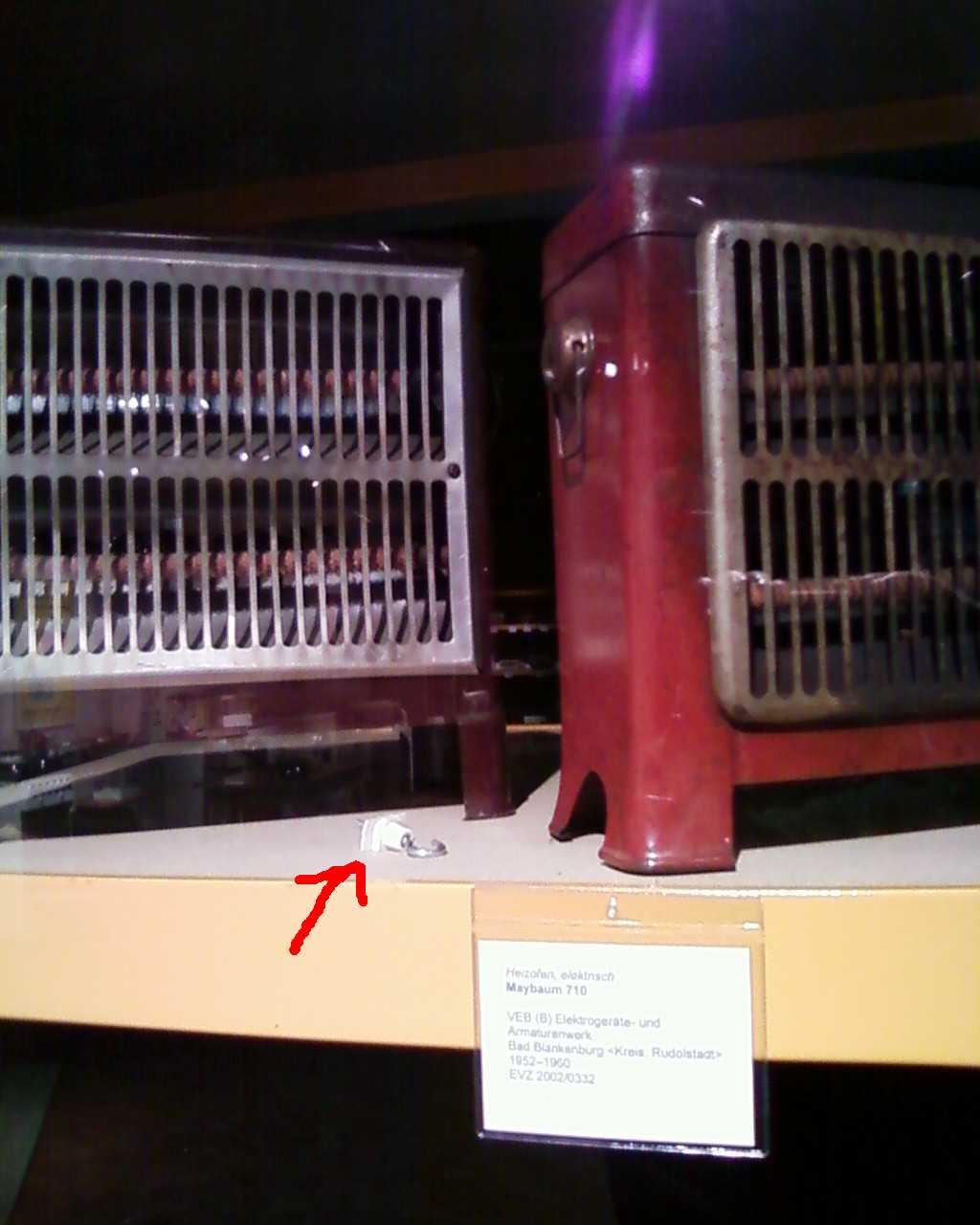

…you discover the reason why one hook in your tool box is missing: because it’s still in the exhibition. Sitting happily between the artifacts. Behind acrylic glass screwed tightly.

All posts by RegistrarTrek

FAUX Real: On the Trail of an Art Forger – Short Notice II

Shhh… don’t tell anybody (well, please do!), but Matt is involved in a great kickstarter film project:

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1041148411/art-and-craft-a-feature-documentary

To quote Matt:

“I am not posting this to get people to fund the film, but so they can get a glimpse of this whole Landis caper and be one of the first to see some of the film and film makers including me! As they will see in the clip as I state, ‘he messed with the wrong registrar’. Tell them ‘Talk soon, Matt'”

Sounds fantastic, please have a look!

Cheers,

Angela

FAUX Real: On the Trail of an Art Forger – Short Notice

Matt is rather busy these days, but he will sure keep us updated, soon.

In the meanwhile, he sent a very interesting link about art forgers where you will find some details you haven’t known until now about Landis:

http://www.intenttodeceive.org/forger-profiles/mark-landis/faux-real-mark-augustus-landis/

Talk soon,

Matt

A Registrar’s Trilemma – The Outcome

I hope you all enjoyed thinking about the situation I presented in the first part and have now decided what you would do.

What was the real outcome?

First of all, you will remember that I said in the first part that real life doesn’t work like an exercise. So, I didn’t have all the pieces of information as well-organized as they were when I presented them to you. I had to draw them together in the continuing process of trouble-shooting – with limited time and with a snowstorm approaching.

As you may have guessed, although option a) (pull out the trucks) was possible in theory, I dumped it pretty soon. It was the most likely to damage the trucks, either in the process of moving or because of weather/climate issues. Imagine moving historical trucks in great haste at the beginning of a snow storm! What are the odds that everybody stays calm and does the right thing? How likely is it that someone loses his head, letting go where he shouldn’t or not watching his step? Preventing artifacts from danger is only one aspect. Avoiding accidents, especially the ones that could lead to injuries, is another and more important to me.

I leaned toward option c) (wait until Monday) at first. Then I checked the webpage of the Deutsche Wetterdienst (DWD, German meteorological service), the precipitation radar and the weather dates of the nearby airport (which is our reference for local weather because it’s only 4 kilometers away).

At the moment we had about 55% relative humidity outside at about -3C. The weather forecast for Monday predicted the temperature would rise to 2-5C with a rain probability of 85%. The precipitation radar told me that the snow front was coming, but was likely to arrive some hours later than the warning time of 10 a.m.

So, I figured out I would have a small time slot for option b) (open gate, place cherry-picker on the outside, work on the inside), because Monday there would be exactly the same problem but with weather conditions worse than today’s. The longer-term weather forecast didn’t give me much hope that conditions would improve within the next week. In fact the -3 °C/55% RH setting seemed to be the best in the foreseeable future.

To double-check my intuition, I took out my faithful Molier hx-diagram. It told me that with this setting I would not reach the dew point in the hall (remember: 11°C/42% RH). The air would first mix, resulting in an increase of temperature and a decrease of relative humidity before the temperature would start descending. And with all artifacts being well heated at 11C, the risk of condensation seemed low (as opposed to what happened some years ago when some smart guy decided to open the gates to let the “beautiful, warm spring air” (18 °C/80%) into the hall (11°C/50%)).

To double-check my intuition, I took out my faithful Molier hx-diagram. It told me that with this setting I would not reach the dew point in the hall (remember: 11°C/42% RH). The air would first mix, resulting in an increase of temperature and a decrease of relative humidity before the temperature would start descending. And with all artifacts being well heated at 11C, the risk of condensation seemed low (as opposed to what happened some years ago when some smart guy decided to open the gates to let the “beautiful, warm spring air” (18 °C/80%) into the hall (11°C/50%)).

If the snow front arrived early, we would still be able to interrupt the work and have the gate closed in about 10 minutes. So, I decided to take option b), but, honestly, I didn’t feel comfortable with this solution and would have been thankful for anyone providing an option d).

We were lucky. The detector was changed within one hour and the snow front reached us as late as 2 p.m. We re-heated the hall very carefully (which wasn’t problematic because the heating system is very weak) and all went well.

Why do I have all the data? Did this happen recently?

Some of you may have wondered why I have all the exact data present although I ran into this situation a long time ago. Cross my heart, I didn’t have to make it up! I just had to look it up.

In general, if there are problematic situations you can talk with experts in your museum or in the field to find the best possible solutions. You can make the decision yourself after you have double-checked with colleagues to see if you haven’t missed something important. Or you can present it to upper management and let them make the decisions. Whatever approach you take, you can say you did what you did to the best of your knowledge. Then, there are situations like this one where you are left to your own devices. You have to decide on the basis of the limited data you have, your experience and your gut feeling.

In these cases it’s important to do a double-check afterwards. Sure, if something goes wrong you know that your decision was wrong and you will do it better the next time. But if all goes well you will never be completely sure if it went well because your decision was right or just because you had an enormous amount of luck. This leads, in the worst case, to do the same thing again next time but with far less luck.

So after the incident, I wrote to many colleagues asking them the question I asked you: “What would you have decided?” It was very interesting to read their responses. In general, they approved of how I acted. Some asked if it hadn’t been possible to take the risk of having only one fire detector active, because since it is infrared it would surely react if there were a fire, even if it was in the other part of the hall. There were a few reasons I didn’t take that risk:

- The two infrared detectors were installed at exactly the same time. If the malfunction had been a production issue, perhaps the second detector wasn’t fully reliable either.

- In case of a fire I was not sure how the insurance would have taken the fact that one of the fire detectors wasn’t activated.

- My main concern was this: What if a small fire were burning for some time in the area of the broken fire detector without the other detector taking notice? The fire could gain strength and when the other one finally did take action, we would have lost precious time for the firefighters to react. The hall was made of stone, so statics were not the main concern. But imagine the amount of oily, probably toxic smoke that would be produced by burning oily wood, trucks and trains, the contaminated air and how it would affect every artifact in the hall. And, at least among colleagues of technology museums, the pictures of what remained of the Nürnberg Transport Museum roundhouse are still present: http://en.wikipedia.org//wiki/Nuremberg_Transport_Museum#Damage_following_the_fire_of_17_October_2005

Some colleagues had additional ideas, such as forming a voluntary fire watch among the staff for the weekend, to see if the weather really would be that bad on Monday, an idea I will definitely keep in mind for other cases to come.

When I was about to write this story down, all I had to do was to dig into my email archive of the year the incident took place under the keyword “trilemma” and there I could re-read all the data and some additional facts I have since forgotten, along with all the suggestions I’d received from fellow registrars and collection managers.

Conclusion

Looking back, there was much to learn from this incident:

- When planning storage, consider how safety appliances can be maintained without putting artifacts at risk.

- Keep all records of past incidents; you never know when you’ll need them.

- Murphy’s Law is still in force.

I hope you enjoyed this little real-life collections manager crime scene, and if you ever feel like sharing one of your stories, we would be glad to publish it on Registrar Trek.

Best wishes ,

Angela

Brought from rough into correct English by Molly S. Hope. Thanks Molly, I would be lost without you!

A Registrar’s Trilemma – How would you decide?

When you are studying museum studies or taking a course in artifact handling and preventive conservation, you learn a lot about ideal storage conditions, improving climate conditions, what to do, what to avoid. However, all exercises you solve in class are clear-cut cases. Normally, there will be one right answer to the question, “What would you decide?”

When you are studying museum studies or taking a course in artifact handling and preventive conservation, you learn a lot about ideal storage conditions, improving climate conditions, what to do, what to avoid. However, all exercises you solve in class are clear-cut cases. Normally, there will be one right answer to the question, “What would you decide?”

Then, there is real museum life. And like real life in general it doesn’t consist of clear cases. You will always run into situations where you have to decide not which solution to a problem is the best but which one is the least bad. Best practice is great but sometimes all you can do is decide between the disaster and the catastrophe.

This is a true story which I will tell in two parts. In the first part I will confront you with a situation, provide you with some additional information and leave you with the question, “How would you decide?” so you can think about the situation until I tell you how the story turned out.

The setting

You are the collections manager of a museum with a large collection of technological artifacts. It’s 7:30 on a Friday morning in December when you receive a call from the maintenance department: A fire detector has caused one false alarm in the night, with two fire brigades marching out. The detector was reset and caused another false alarm early this morning. It needs fixing.

The storage hall is provided with two similar infrared fire detectors, each one controlling one half of the hall. In order to fix it, the fire detector must be checked and eventually replaced by an external service technician and can only be reached using a cherry picker. The place where the cherry picker could stand inside the hall to reach the fire detector is blocked by two large historical trucks.

Alternatively, when one gate is opened, the cherry picker can stand outside the hall reaching inside and the technician can work from there. As a result, the temperature inside the hall would drop from 11C to around zero next to the gate, and a little more in places further down the hall.

Storage hall climate conditions

- Artifacts stored in the hall are trucks and railway material

- The temperature in the hall is 11 degrees Celsius

- relative humidity is at about 42%

Weather conditions

The local weather station currently reports a reading of -3C at 55% relative humidity, and the weather is overcast but dry. There is a weather warning by the meteorological service for heavy snowfalls, approximate starting time: 10 o’clock a.m.

The weather forecast for next week: on Monday, the temperature will rise to 5C with an 85% chance of rain. The weather will stay warm and wet for the next one or two weeks.

Telephone messages

FFS – Fine Fire Services, call 7:56 a.m.

A service technician can be there at 9 a.m. Work on the fire detector will take approximately 1 to 2 hours, depending on whether the detector needs only to be cleaned or completely replaced. The workers would have be notified by 10 a.m., otherwise they would not be able to come until Monday morning.

Conservator Trucks&Cars, call 7:59 a.m.

Trucks can be moved, but need heavy equipment and support from maintenance department.

Head of maintenance department, call 8:05 a.m.

Tow bar and truck able to pull the historic trucks are available; staff to help the conservator is available.

Conservator Trucks&Cars, call 8:07 a.m.

Where to pull the trucks? The only possible place is the forecourt outside the hall. How long will it take to pull them there? If work begins immediately, they can finish by approximately 9:30 a.m.

NOW IT’S UP TO YOU

Do you have all the information you need to make a decision? How would you go about deciding?

a) Pull the two trucks out of the hall so the technician can work inside?

b) Open one gate so the cherry picker can stand outside and the work can be done inside the hall?

c) Wait until Monday or later, leaving 50% of your hall without a fire warning system, until the temperature rises and it will be dry?

Now, my dear readers: How and what would you decide?

Happy anniversary, Registrar Trek!

On January 2nd 2013 we started a project with the purpose to inform the public about collections work and bring collections people around the world together. Now, a year later, we are a team of four authors and 32 translators from 19 countries, providing 16 languages.

On January 2nd 2013 we started a project with the purpose to inform the public about collections work and bring collections people around the world together. Now, a year later, we are a team of four authors and 32 translators from 19 countries, providing 16 languages.

I guess you, our faithful readers, are more interested in what we have in stock for the next year of Registrar Trek than in statistics*.

First of all, be insured that we will keep you entertained with stories and articles from the world of collections management. And we are happy for every new contribution you will send in. Our plan is to hunt for more practical hands-on stories, examples of good practice in registering, good storage solutions and smart ideas in documentation and collections management. We will even have some real world stories that will end with questions like “How would you decide?” leaving you with the possibility to chew on the problem until we reveal the outcome in one of the next posts.

Matt will keep us informed about art forger Mark Landis and his aliases, Anne has some more to tell “off the shelf” and Derek will take you all into the fascination of registrar’s work. Angela is planning to launch a small fun series called “The Museum of Spam”.

And of course, there will be stories and articles from guest authors. We’ve actually got one in the pipeline from a data base enthusiast and there are several others promised.

So, stay with us and stay tuned!

Your Registrar Trek Team

* Statistics: We published 62 posts, had 12,000 visitors who visited our blog nearly 20,000 times. Over 300 subscribed to our RSS-feed.

This post is also available in Italian, translated by Silvia Telmon.

Season’s Greetings from Registrar Trek

This year is different. Christmas „catches“ me in the middle of the installation of our upcoming special exhibition, on electrical household appliances. Last year was packed with taking care of vacuum cleaners, pressing irons, food processors, hair-dryers, coffee makers… well over 1500 objects were picked for exhibition, many more were researched and their data corrected in the data base. Now everything must be put in the right place, get individual treatment (i.e. fixing of loose parts or cleaning) and a correct label. No contemplative working process that invites reflectiveness. But I don’t want to leave for the holidays without my own personal review and outlook, especially because this time I can share it with colleagues all around the world:

Aside from the challenges of the aforementioned collections exhibition the last year was defined by the start and growth of Registrar Trek. We went live on January 2nd and I’m sure that there will be time for a special review on our first anniversary. It’s great to see how a weird idea from two people has developed within one year into a project that is known and supported by so many colleagues around the globe.

Those who are in permanent contracts feel the growing pressure of taking over more responsibilities because the work must be done with fewer colleagues and declining budgets. Combining professional ethics and financial needs is a difficult task. Amidst of all this trouble, let us not forget that the collections field is not the only one affected by the crisis. I have seen many discussions on professional groups and listservs about how money is spent on the wrong things and wrong projects, and it seems to me that every colleague envies the other for funded projects. Personally, I feel that’s not a successful approach. As registrars, collection managers, curators of collections or documentation officers we are in the same boat as conservators, educators, guides, guards, curators, marketing people… The boat is called „museum,“ and we will need each others’ skills to avoid shipwreck.

I’m really glad that the Registrar Trek Team does consist of so many professions: there are of course registrars and collection managers, but also conservators, curators, marketing specialists, visitor guides and people from totally different fields. This variety keeps the exchange of thoughts interesting and the development of this project joyful. For the upcoming year, we have more exciting stories and articles in the pipeline, so stay tuned.

Now I’m going to gather some waste and stack a few pallets before I leave for Christmas. But before that, in the name of the whole Registrar Trek Team:

We wish you Merry Christmas and a happy healthy and successful New Year 2014!

Angela

This text is also available in Italian translated by Silvia Telmon.

Update: Art in Hotels

Sometimes we receive feedback regarding our articles on Registrar Trek from the farest regions of our planet. But last Monday it was feedback from just next door:

“Guess what I saw this weekend?” Dr. Hajo Neumann one of our curators asked me.

I was clueless.

“Hotel Art!” he grinned and showed me this picture:

Yes, folks, someone actually nailed the picture directly to the wall! So close the whole frame bends. That it was hung so close to the window that it gets all the UV exposure it can possibly get is a nice extra.

Art in Hotels

For the record: I love hotels. And I think museums could learn a lot from them about making visitors feel welcome. But there’s one thing that continually catches my eye from a professional point of view. So allow me to share a few words today on the topic of “Art in Hotels.”

Art in hotels is great. Art can comfort those who are feeling lonely. It can lead to new discoveries and awaken treasured memories. Art can be inspirational, and it can have a calming effect after a hectic day. But art can also do the opposite: it can make a hotel guest feel extremely uncomfortable. I experienced the following examples myself, during one long weekend in various hotels.

1. The Subtle Horror of Heirlooms

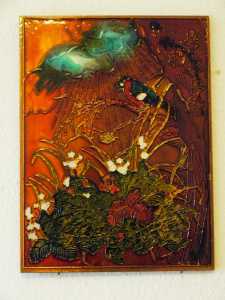

Nothing is nicer than art we inherit. There are often real pearls in the well guarded treasures of our ancestors. There is, however, a simple rule of thumb: if you must remove something from your house because it gives your grandchild nightmares, it’s hardly appropriate to hang it in a hotel room instead:

A nature scene in copper? Perfect for a country hotel! What’s not to like?

After all, what says “Welcome” better than the dead eyes of a zombie-bullfinch (Pyrrhula pyrrhula)?

2. You’ll Hang Right with Us!

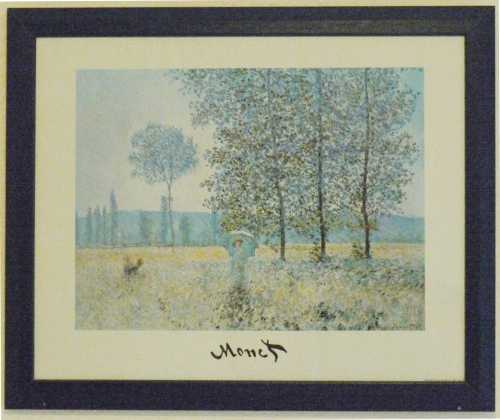

A while ago, a clever publisher of art posters had an idea: In a society in which we can no longer be sure that people will recognize art when they see it, a little help might be required. So he supplied reprints of famous works of art with enlarged, stylized signatures of the artists—“Vincent,” “Monet,” “Manet,” etc. It seems like hotels are fond of this kind of art print, and I bet you’ve already seen this on one of van Gogh’s sunflower bouquets or another. In one hotel I had Monet’s “Fields in the Spring” above my bed.

The original is undeniably a masterpiece of Impressionist art. Yet in this case it was a picture under which no registrar could ever sleep well. You can see in the first photo that the colors have faded after years of exposure to UV light. But the true horror doesn’t become apparent until the photo with flash.

The environmental conditions in the hotel room were obviously anything but ideal. As if that weren’t enough, the frame was secured in a manner I have not often seen before. Unfortunately, the lighting was too dim to document this sufficiently:

The picture was actually nailed to the wall through the frame… In the hotel’s defense, the room was otherwise fine and the food was excellent.

3. Do You Have the Monet in Apricot?

Art reproductions have enjoyed a long and honorable tradition. They present us with the opportunity to be surrounded by valuable art without having to spend huge amounts of money on it. Naturally, one usually chooses the work of art to suit the room. Recently, though, I noticed some hotel art that turned this principle upside-down: instead of finding art that suited the room, the art was made to suit it.

Sometimes sections are extracted from masterpieces in ways the artists never originally intended. For example, there’s the woman with the umbrella in the aforementioned “Fields in the Spring,” extracted, enlarged, and in portrait mode. She fits better in the corridor that way, and there isn’t so much unnecessary undergrowth in the picture… In an extreme example, the colors are adjusted to make them a better match with the wallpaper.

Another annoying custom is mass production made to look like real paintings. Closer examination reveals these to be inkjet on canvas stapled to boards made to look like a stretcher frame. This kind of mass-produced art can be found in any style (particularly popular, for example, is something based on Edward Hopper for fast-food restaurants), and abstract themes are especially common. Presumably because they’re extremely low-maintenance: they’re considered intellectual from the start and can be produced in any color imaginable. And whoever finds a motif that can hang as a matched set over a double bed wins:

Whether it’s really art is debatable. In this case, I think someone went through a catalog looking for décor to match the room. And the fact that you can’t borrow a level from the reception desk to get them hung straight, at least, was the final straw.

I can’t exclude the possibility, however, that the hotel owner especially liked the piece shown above. Beauty ultimately lies in the eye of the beholder. Still, even if you like something a lot, so much so that you can’t get enough of it, a hotel owner should never make the mistake—even with mass productions—of hanging the same piece in two places to which the same guest has access!

I find it amazing that they managed to hang both sets nearly identically crooked!

Sleep well!

Angela

Translated from German into English by Cindy Opitz.

This text is also available in French translated by Marine Martineau.

A Captain Leaves The Ship

There are good days and there are bad days. This is a bad, sad day. A day I hoped would never come – or if it did, then in the far, far future when Registrar Trek is a myth the old registrars tell the young registrars about.

There are good days and there are bad days. This is a bad, sad day. A day I hoped would never come – or if it did, then in the far, far future when Registrar Trek is a myth the old registrars tell the young registrars about.

This project started out as a project of two people: Fernando and me. We had been exchanging thoughts for … well, almost exactly a year. We laughed, had fun, inspired each other and out of this, Registrar Trek was born. A small project at first. Two people writing articles and translating them in their mother tongue. When we went live in January, we soon gained more authors, translators and more languages. Registrar Trek grew rapidly, up to 37 contributors.

Rapid growth is great, but it’s difficult to keep an eye on everything. So, while I was busy managing new team members, adding translations and writing stuff, I didn’t notice that one team member was not happy with how things were going. A very important team member, my Captain (we often joked that his role model was Captain Jean-Luc Picard and mine was Admiral Kathryn Janeway).

The problem with working with team members from all over the world via internet is that you don’t meet people face to face. In the normal museum business your eyes or your intuition tell you that something isn’t understood the way it is said or that one team member is not happy. When this occurs, you could grab two cups of coffee, close the office door and sit down and talk. On the internet you have to rely on what you read from others, a very limited view of what is going on in another human being.

Maybe it was words I wrote that weren’t understood the way I meant them, maybe it was other things I did or said (or didn’t do or didn’t say), but the fact is that Fernando has decided to leave the Registrar Trek. No chance to reach him, no chance to set things straight, no chance to hold him back. I always said that if one of us stopped having fun, this would be the end of Registrar Trek. And in a way I still feel I don’t want to steer that ship without my captain, co-founder and co-administrator. So my first impulse was to close the project down.

But then, there are all of the great colleagues who offered their help with translations and the many people I know are working on contributions for Registrar Trek. And of course there are you, the readers of the blog, who keep us motivated to invest our free time in articles and translations. So, I feel a responsibility to carry on. I can’t promise that we can do it as well as we did before. Now, the captain is missing! But we will carry on.

Angela