by Rupert Shepherd

If you were given a choice between donating money for museum conservation, education, or documentation, would you give to documentation?

I was offered this choice by a collecting box at one of the London national museums just before Christmas last year. Or rather, I was given a choice between conservation and education: documentation didn’t feature. This made me think: documentation seldom appears in public discussions of what museums do.

Horniman Museum Collections Assistant Laura Cronin at work reconciling one of the mummies with its paperwork. Photo: Helen Merrett

If you’re reading this blog, then I think you already know what documentation is. For what it’s worth, my definition falls into two parts. Documentation comprises: looking after the information a museum has about its collections; and making sure that the museum is able to account to its public, its funders, and anyone else for its collections and everything that happens to them. And I’m sure you also understand that a museum’s documentation is as central as its objects to everything it does: without documentation, the collections are a meaningless pile of odds and ends. If we don’t know what the objects are and where they come from, we cannot meaningfully display them or help people understand them.

Why, then, does documentation so seldom appear in public? After my encounter with that collecting box, I thought I’d ask my colleagues across the museum community, so I started a discussion on LinkedIn, in Collections Trust’s Collections Management group (you need to have joined the group to read it). The discussion was fascinating, and this blog is really an attempt to pull it together into something more structured and condensed.

Why is documentation important?

In the UK and, I expect, around the world, publicly-funded museums are under great financial pressure: we’re expected to do as much work as we’ve always done – if not more – with less and less money. As a result, we need to look more widely for funding even for our core activities. A few months ago, I was talking about the difficulty in funding day-to-day documentation work with my museum’s director, and she said something which I’ve taken to heart: ‘you need to tell the story’. There’s no point continually saying documentation’s important: we have to say why it’s important.

In an attempt to provide a really inspiring argument for documentation’s significance, I asked people in the LinkedIn group to provide their explanations – ideally, in the 140 characters or fewer needed to create a tweet. (There’ll be more about Twitter later.) There were some great, pithy responses, and a few weeks ago I tweeted one of these a day for a couple of weeks. I’ve Storifyed them here. They pretty much reinforce what I said before: without documentation, we can’t understand or do anything meaningful with our objects, and so we can’t use them to do all those inspiring things we pride ourselves in. And, of course, we need to know where our objects are, be able to prove that we own them, and so on.

Hidden treasure revealed during the Horniman Museum’s Collections People Stories collection review: a pendant in gold, copper and semi-precious stones from Nepal, 1970.292. Horniman Museum and Gardens

One or two contributors took the wider view: Registrar Trek’s own Angela Kipp said that ‘without documentation, humanity loses its memory’ – and ‘losing your memory means losing yourself’. And perhaps my favourite, for its sheer enthusiasm, came from Barbara Palmer, registrar at the Powerhouse Museum: ‘I uncover hidden treasures and make them accessible. I feel like I have the best job in the world.’

Why isn’t documentation more visible to the public

(and why does this matter)?

But is this the right way to proceed? Nick Poole, for one, suggested that we shouldn’t be dividing museums up into separate activities like this: what is important, he said, is the end result. After all, supermarkets focus on the quality of what they sell, not on how it got to their shelves.

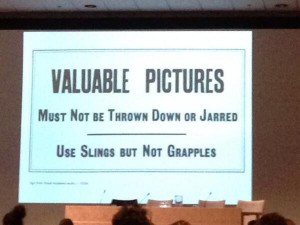

But with all respect to Nick, I think this misses the point slightly. In many other fields, the infrastructure is visible: to stay with Nick’s example, supermarkets advertise the freshness of their produce by saying things like ‘from the farm to our shelves in two days’, and we can all see supermarket shelf-stackers and the trucks that carry the produce across the country. In museums, we show off our exhibitions, displays, interpretation, and websites – but visitors can’t see the infrastructure used to create it. When do we ever say ‘this exhibition was brought to you using the quality data in our collections management system’?

And should we be comparing museums to supermarkets anyway? Angela reminded us that museums exist not just to display objects, but also to educate, collect, research, and preserve our objects for future generations and researchers: we all know that not everything we collect ends up going on view to the public straightaway, and much of the research done on the collections does not lead immediately to a new piece of public interpretation. But in the UK, at least, I can’t help feeling that Angela’s is a somewhat unfashionable view: we are constantly being asked to justify what we do in tangible, measurable and visible ways, hence the focus on the public outputs.

‘Mr Horniman’, holding a specimen of his butterfly, Papilio hornimani, talks about the collections in the Horniman Museum’s African Worlds Gallery. Horniman Museum and Gardens. Photo: Laura Mtungwazi

Other people, such as Michaelle Haughian and Shaun Osborne, suggested that documentation was primarily of interest to other museum people: the public don’t need to see how it works. Michaelle wondered whether ‘the crux of this issue isn’t the way funds are allocated? Do we need to have a second discussion about the bare bones funding models museums are accustomed to? Do we need to talk about why education and programming seem to get more money than collections or registration work?’ This is a point that Angela also made: ‘people decide to fund what they know, see and take part [in] in museums (educational programmes, tours) and not something that is hard for them to imagine, because it needs explanation (conservation, documentation, public relations, administration…).’

I think this is the fundamental problem: if you don’t know something exists, how do you know that it’s important, let alone that you could fund it? And perhaps, as Shaun also suggested, what’s important is not that documentation should be made visible to the public, but that it should be made visible to our senior managers, our trustees, and our funders.

Why is documentation a ‘problem’

(and how did we get to where we are today)?

Nick also suggested that one problem we face when making the argument for documentation is that we tend to see it as a problem: we have a horrible tendency to append the word ‘backlog’ to it. Thinking about my own organisation, the Horniman Museum, we do have backlogs of various kinds, and I would certainly say that they are problems: one reason I’ve been concerned about documentation’s public profile is my wish to clear some of the backlogs which are preventing my museum from working as efficiently as it might. In the current funding climate, we have to work as effectively as possible: poor documentation hinders this; really good documentation enables it.

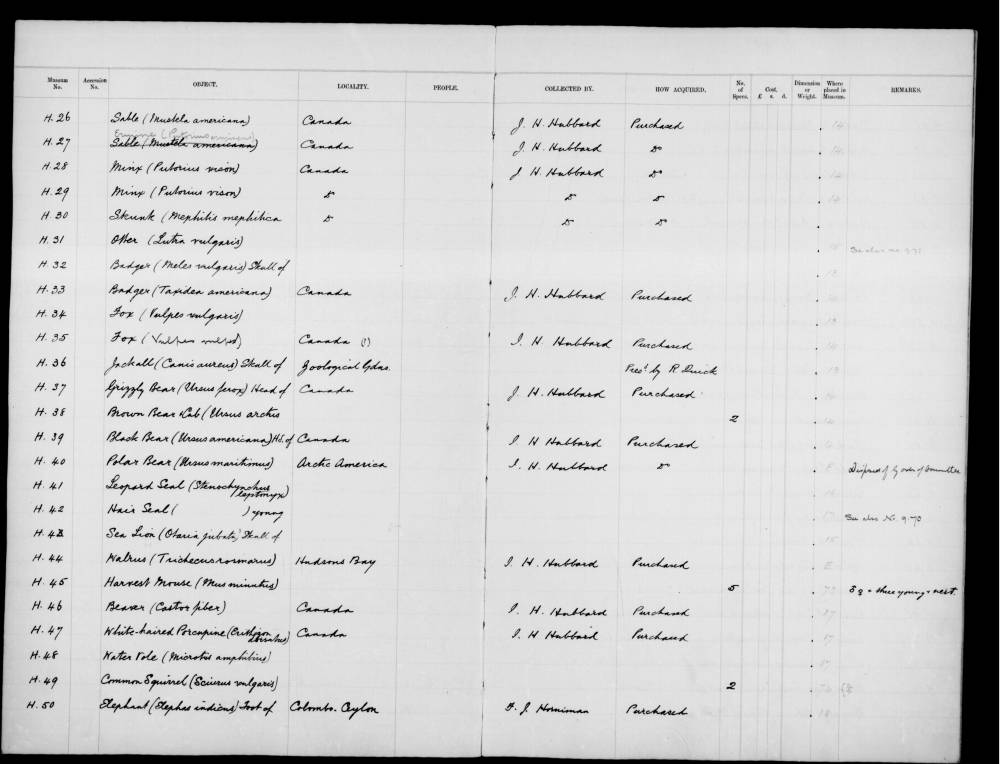

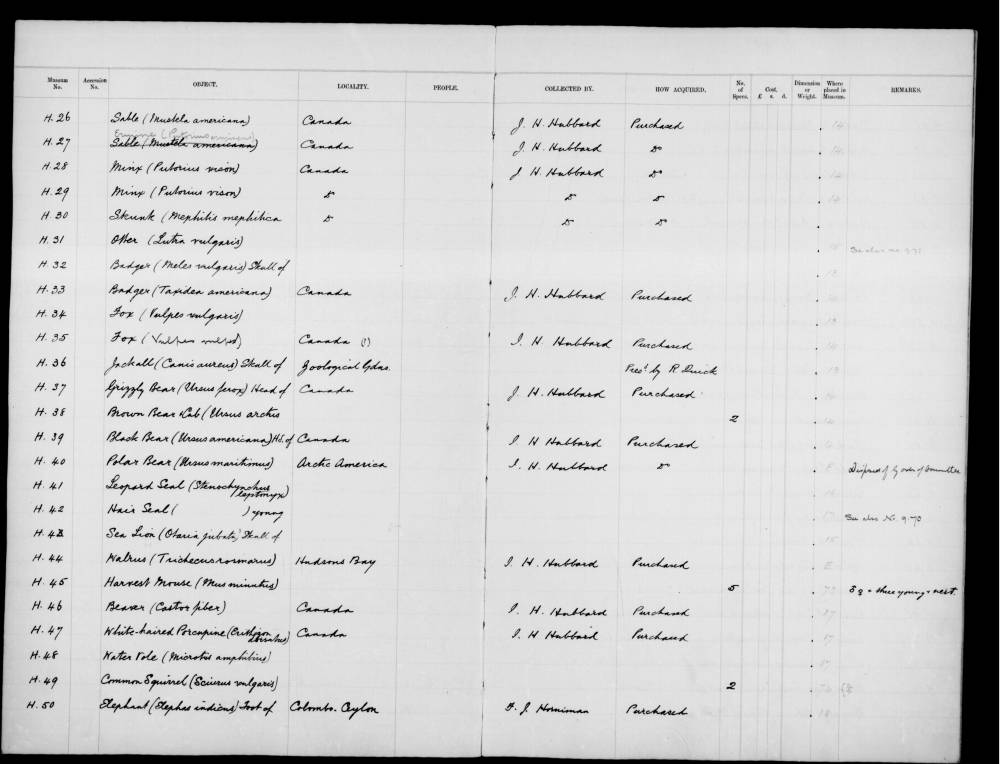

A page from the Horniman Museum’s register of natural history specimens from 1900 to 1934, ARC/HMG/CM/001/008. Horniman Museum and Gardens

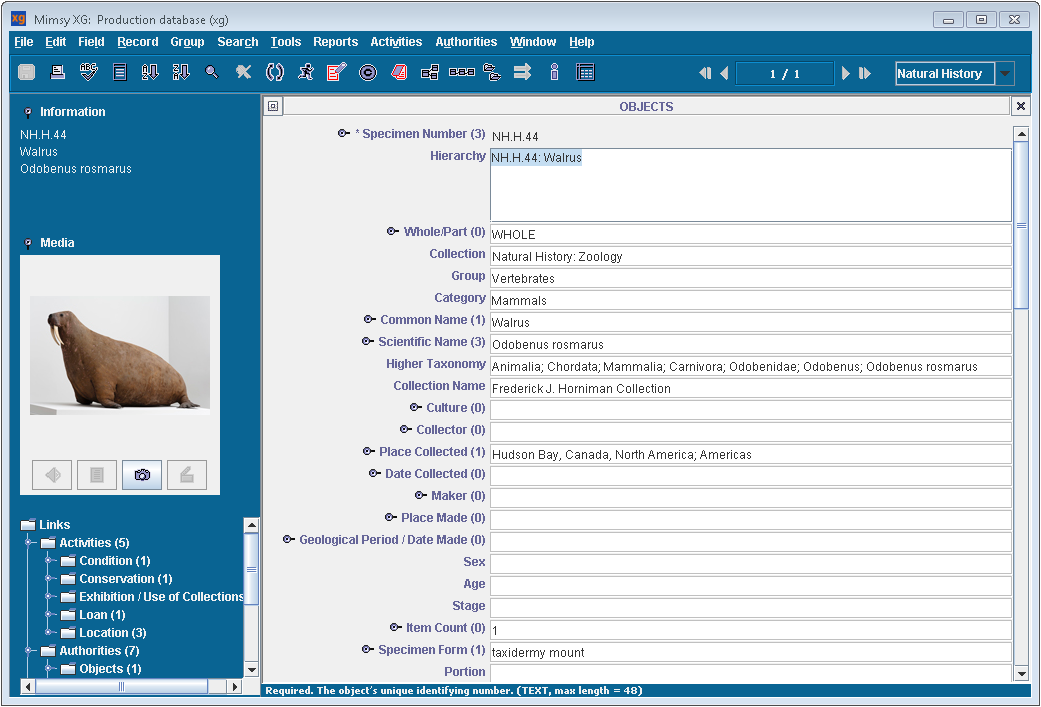

Backlogs arise for various reasons. At least in older museums, they exist in part because of the way our current data has been generated: from what I know of my own institution, our records started as register entries, which were expanded into index cards, which were built upon to form catalogue cards, which were imported into an early database, which were in turn imported into MultiMimsy, which were then imported into Mimsy 2000, and then imported into Mimsy XG. (At the Ashmolean, over 200 separate databases were imported into their first museum-wide collections management system, MuseumPlus.)

Every stage represents an opportunity for inaccuracies to creep in (in the manual conversions), and kludges to be made when importing or transferring data (in digital systems) in order to get something up and running in a reasonable time. We always promise ourselves that we will come back to it and tidy it up; and then something else comes up, the opportunity has gone, and we have – a backlog of data tidying.

And this leads to a second reason why backlogs build up: straightforward lack of resources. Museums simply don’t have the people needed to do the work that needs to be done (particularly, that needs to be done now if we’re to create records that we don’t have to keep coming back to). In many organisations, as documentation tasks are increasingly passed to volunteers, placements or interns rather than paid staff in an attempt to get something done, so more of the work needs to be checked and revisited to ensure it’s fit for purpose; and we don’t always have the time to do that as much as we would wish.

Why has this all become so labour-intensive? Graham Oliver, who’s worked as a curator for 35 years, reminded us that documentation used to be part of a curator’s work – but the people contributing to the LinkedIn discussion were called ‘curator, documentation officer, collections information systems manager, content manager, access officer’, and so on. The last two or three decades have indeed seen a huge increase in specialisation in the museum world. When documentation consisted of registering an acquisition, creating index cards for it, pulling one’s research into a history file, and updating a location card when the object moved, it was easier to incorporate it into one’s day-to-day curatorial work.

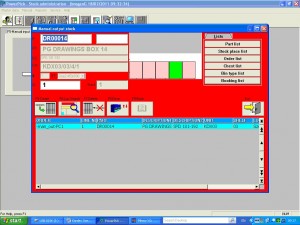

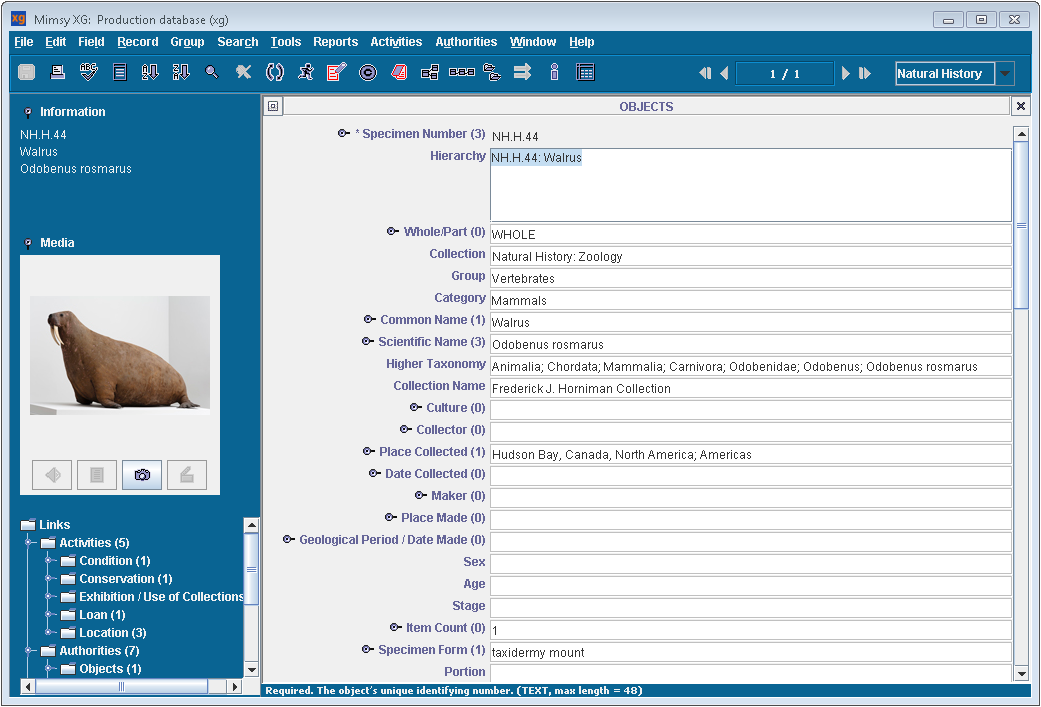

An object record in the Horniman Museum’s Mimsy XG collections management system. Horniman Museum and Gardens

But then computers arrived, and they became the preserve of specialists – understandably, if you look at a system like Mimsy XG, which we use at the Horniman: there are something like 3000 different, discrete units of information in there, and to configure it, maintain it, and keep the data consistent is a specialist job which the vast majority of people who work in museums simply wouldn’t want to do. So documentation jobs were created to manage the information, and to make sure that the procedures drawn up in Spectrum over the last 20-30 years were being implemented and tied into the computerised information: suddenly, there was a new sub-discipline within museums. Many curators took to it; others, alas, didn’t. The same is true of the many other specialists doing the work that used to be done by curators – and there were far fewer curators then, than there are now staff doing all those specialised jobs.

And as documentation has become more and more of a specialism, other museum staff have become less aware of some of the problems which can arise if it’s not done just right. There are a couple of misunderstandings which I think have been particularly pernicious, and have made it much harder for us to argue for resources to address our backlogs.

The first is the database pixie delusion. A senior curator (I’m naming no names, not even institutions, here) once said to me that their ideal collections database would comprise one field, into which they would type what they knew about the object. The database would then organise this information so it could be used effectively. The delusion is the belief that you simply have to put your collection information into a database and everything will be all right. It doesn’t matter that the data is inconsistent, mis-spelt, or incomplete: it’s in a database, so of course it’ll be OK. After all, the database contains little pixies that will get the data tidy (even proof-read it), consistent, linked, and so on. Our colleagues sometimes seem to have had a touching faith in the intelligence of computers, whilst those of us who work with them more frequently know that they are fundamentally dumb, and that if you put rubbish in, you’ll get rubbish out.

Related to this is the Google delusion. We’re now very used to using web search engines to find information. We type something into Google, say, and if we get one useful result in the first page, we reckon it’s worked pretty well. On the other hand, in a well-maintained database, if you run a search, your results will be all the objects that are precisely what you are looking for, and no others.

Again, this reminds me of a conversation I once had with a colleague. We were talking about searching for objects made of copper alloy, and how one would run the search. Ideally, you would enter ‘copper alloy’ in a materials field, and get back all those objects made of copper alloy, and no others. But my colleague was quite happy to run a series of separate searches, for ‘copper alloy’, yes, but also for ‘Cu alloy’, ‘CuA’, ‘bronze’, and so on: in their mind, if they were able to do this and get back most of the relevant objects across all these searches, along with some others which weren’t really relevant, the database was working well. They didn’t seem to realise that this made it much harder to then reuse that information by generating reports or lists of objects which could be used outside the system.

If we return to Google and think of the amount of research and development that has gone into its search algorithms, then we can see that it’s a massively expensive tool for indexing really poorly-structured data, and it does so adequately, at best. It has lowered our expectations of data retrieval in an extremely unhealthy way.

Raising documentation’s public profile

As you can see, I agree with Nick when he says that there’s been a long-standing culture clash between documentalists, who tend to be systems thinkers, and our colleagues who are, as he says, ‘value-driven creative people with a strong set of social values’. This has led to the need to explain the value of documentation in terms of its end users. I’d also agree with Nick that we need to argue for a museum and funding culture that recognises that ‘a building with things in it, but without knowledge or skilled people, is not a museum. And people deserve museums.’

Horniman Museum Collections / Documentation Assistant Clare Plascow (back to camera), and Documentation / Collections Assistant Rachel Jennings, explaining their work on the Collections People Stories review to a ‘behind the scenes’ tour of the Museum’s stores. Photo: Nicola Scott

So we come back to how best to make those arguments. As we’ve seen, our LinkedIn discussion broadly divided into two camps: first, those who feel that it’s not worth raising documentation’s profile to the public, because it’s part of a process that leads to public outputs like displays, exhibitions, engagement or learning events, and those end results are what’s important; and second, those who think that it is worth publicising what we do for its own sake. There was also a group who suggested that documentation should be bundled up as part of general presentations of ‘behind the scenes work’, and this in particular is something that I think we could all try and pursue.

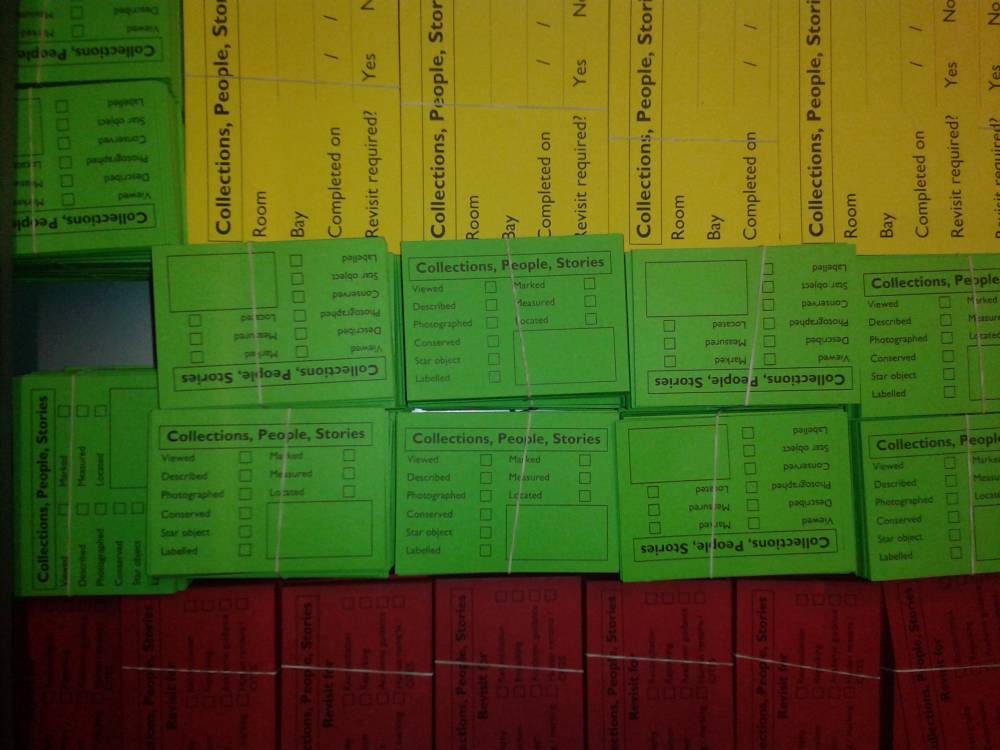

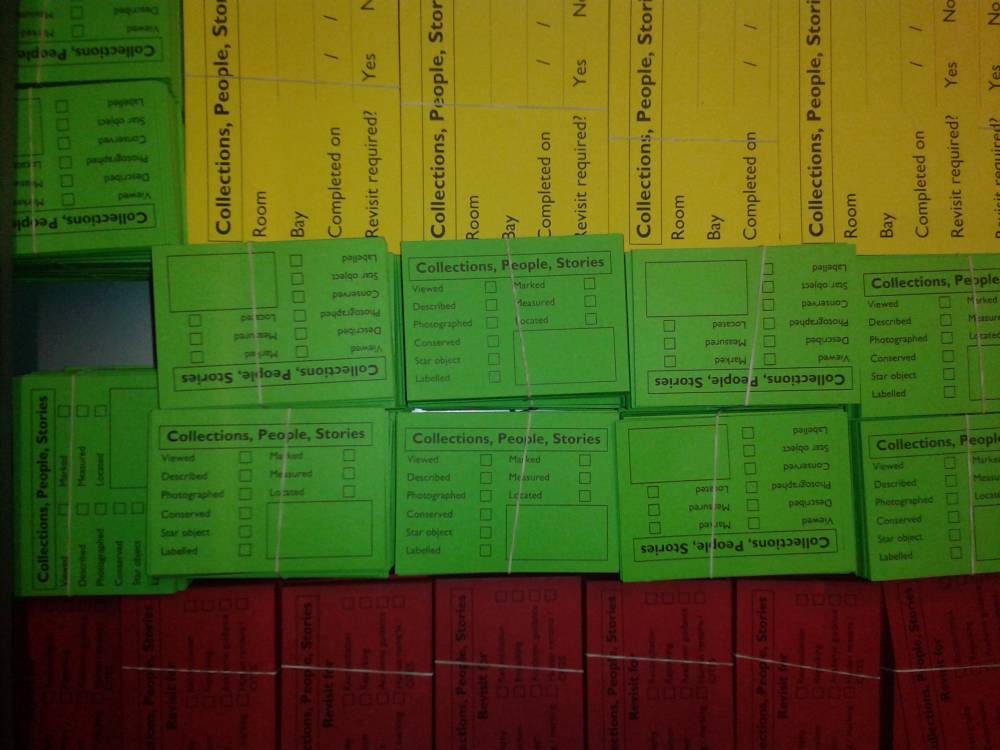

Box and bay labels for the Horniman Museum’s Collections People Stories review awaiting use. Photo: Rupert Shepherd

But generally speaking, I think I’m still part of the second group. Something else that persuaded me to start the discussion was a passing comment when I was in a meeting. One of our conservators said that work had just been finished on an object, and our Digital Media Manager’s immediate response was ‘Great! Can you write me a blog about it? Everyone loves a conservation blog.’ Our conservation department has its own page on our website, linked to ten case studies. Our Documentation (and Collections Management) departments don’t – even though we’ve been making significant contributions to aspects of the museum’s work as diverse as our online collections, our Collections People Stories collections review, and our famous walrus’s recent trip to the seaside at Margate.

Like that national museum’s collecting box, this showed me that we do publicise our behind the scenes work – but only certain parts of it. And as Angela said, what’s visible is what people think of funding when they reach for their cheque books. Yes, we need to raise documentation’s profile with our managers; but we also need to spread the word more widely, because in the end, it’s not just our managers who provide our funding.

So how can we do this? When I started the discussion on LinkedIn, I also suggested that everyone working in museum documentation who had a Twitter account should tweet what they’ve been doing each day, and – crucially – why it’s important, using the hashtag #MuseumDocumentation. A couple of weeks after we began, Angela Storifyed some of the tweets; and you can also follow them here:

Even if our followers are only our family, friends, or colleagues, it’s a start; but the more momentum we can gather, the more word will spread beyond our immediate circle; and our managers, and perhaps even our funders, will start to understand that documentation really is worth supporting. So I’d like to take this opportunity to thank everyone who’s contributed to the discussion so far, both on LinkedIn and on Twitter: I’ve been hugely impressed by everybody’s enthusiasm for, and dedication to, what we do. I’d also encourage everyone else to have a go at tweeting about #MuseumDocumentation: I’ve found the experience of saying why what I do is important, in a new way every day, quite challenging – and stimulating.

Has it been working? Well, our Digital Media Manager did come through and ask me to write a short blog post about documentation and the hashtag for our website; and I have been interviewed for an article on documentation to go in the Museums Journal, as well as being asked to write a short piece for the Museums & Heritage Magazine. So maybe we’re beginning to raise our profile a bit.

Oh – and when I went back to that London national museum, the collection box no longer offered you a choice ….

About the author:

Rupert Shepherd initially trained as an art historian, specialising in the Italian Renaissance, before moving into museum documentation, dabbling in humanities computing and digitisation along the way. He was Manager of Museum Documentation at the Ashmolean Museum for three years, and since 2010 has been Documentation Manager at the Horniman Museum and Gardens in south-east London – but the views he expresses in this post are his own.