Objects Containing Ingredients in Collections

Recently I stumbled upon this article on Piero Manzoni’s work “Artist’s Shit”: https://www.sartle.com/artwork/artists-shit-no-014-piero-manzoni

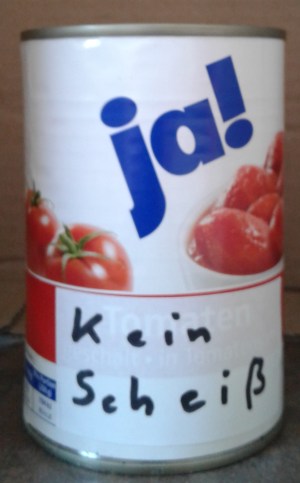

It reminded me of a problem that hits every collections manager at least once in his or her career. The object that contains something. Not always the content is as debatable as canned crap, but from arsenic to zwieback there is an endless list of ingredients that can give you headaches for various reason. Now, what does the responsible collections manager do in those cases? It sure doesn’t come as a surprise that he or she is asking a variety of questions before he or she decides what to do.

Does it fit into the collection?

Your mission might say that you are collecting Italian art from 1960 to 1970, so Piero Manzoni’s work might well fit in there. But your collections policy might limit this down to paintings and works on paper for the reason that your storage is only suitable for these materials and you don’t have the capacity to store sculptures or other three dimensional objects. In this case, a can of artist’s you-know-what is luckily none of your business.

What’s important? The container, its ingredient or both?

If you come so far that the object fits into your collection, the next question is if this holds true for all of it.

If you are a museum for industrial design chances are you want to preserve the container. If the can held meat extract instead of this artist’s… product… you would probably have no problem with carefully opening and emptying the can in the least invasive form possible to preserve the original design of the container.

If you are a museum whose mission is to educate people about feces (nope, I so totally didn’t make this up: https://www.poomuseum.org/ ) and therefore you preserve that stuff, you might likely be more interested in preserving the ingredient than the container. In real collections life, this often means that you have to remove the content from the original container to store it in a more appropriate container for long-term preservation. Now, I haven’t done any research on this concerning human feces, but my gut feeling tells me that a tin can is probably not the best container for their long-term storage.

Then, there are the cases where both, ingredient and container are worth preserving. I think we are safe to say that this is the case with “Artist’s Shit”. The age long questioning if Piero Manzoni really did it, if the can really contains what is said on its label is a strong evidence. A container just saying “Artist’s Shit” but obviously being empty would be somehow pointless. So would be preserving Mr. Manzoni’s feces, I guess. Although I’m not completely sure about this. Some future art historian might be interested in having it analyzed in a lab to find out about the artist’s lifestyle habits. After further consideration: it MIGHT be worth preserving it, as long as it fits into your collections policy and you solved the issue of long-term preservation.

But in this case, both, content and container form the artwork, so we certainly want to preserve both. And for that matter, we can’t separate the container from its ingredient, even if feces might demand other storage conditions than tin cans. We would alter the original condition of the artwork, which we strive to avoid as museum professionals. As a side note: countless collections managers have missed the chance to become artists themselves by leaving Manzoni’s work untouched – someone did open a can and it is now an artwork itself: http://beachpackagingdesign.com/boxvox/opening-can-boite-ou%C2%ADver%C2%ADte-de-pie%C2%ADro-man%C2%ADzo%C2%ADni

Is it hazardous?

It’s one of the key questions for every collections manager. The question goes different ways: is it harmful for itself and the other collections items and is it harmful for those working with the collection? On a sad note, I never, ever encountered a collections manager who is asking these questions in a different sequence, although, really, we should!

The question if it is harmful for itself is one that also plays a role when deciding on whether or not separating the ingredient from the container. Some things can destroy themselves if locked in an air-tight container. I’m sure every museum with a collection of celluloid items has a story about it. Concerning feces I would consider this risk rather low. However, I’m not an expert.

Whether or not the object is a threat to the rest of the collection is a key question before accepting an object. As there is quite a bandwidth of dangers that range from highly dangerous to mostly harmless under most conditions this kind of risk analysis can keep a collections manager up all night.

In the case of Manzoni’s artwork… well, there is a certain possibility that the feces inside (if they are inside) start fermenting, especially if it is too hot in the storage. There is a certain likeliness of the artwork becoming a fragmentation bomb under these circumstances. This could be avoided when stored properly.

The hazard for people handling it goes into the same direction. However, the risk is not so high that it would justify denying the acquisition (like it would probably be if someone offers the museum some live chemical agent). There should be a written procedure for the handling, for example containing that staff should check the can regularly for swelling. It should also be noted that there is a potential biohazard as we don’t know if there are real feces inside and we can’t be completely sure that Manzoni was in the best of health when he… safety first, right?

Summing up

After the collection manager knows

- if the object fits into the collection,

- if the content and its container are worth preserving,

- if they can be separated of have to stay together unaltered, and

- if they are hazardous and what these hazards are,

the collections manager will

- advise on whether or not to acquire the object,

- store the container and its ingredients in the most appropriate way,

- label hazardous objects if necessary, and

- write handling procedures for future colleagues.

I desperately tried to find a closing sentence for this article that is not a bad pun or for other reasons inappropriate. I failed. So I just write: Stay safe!

Angela