Nowadays everybody seems to be obsessed with numbers. Big Data, KPIs, ROI, people like to count and somehow they believe that only if they have counted enough numbers they can make sense of what’s going on. Recently someone asked how many artifacts are needed to justify a curator’s position. People ask ”How many artifacts does your collection hold?” as if this information says anything about how significant or valuable the collection is or how good it is cared for. Data base entries done to achieve unrealistic “objects per day/month/year” goals instead of focusing on the quality of the entries let me bang my head against the wall pretty often.

I could argue for hours about what is wrong with those approaches but I guess you, our readers, could do it just as well. Instead, I tried to look at it from a different angle: We, the collections people, deal a lot with data every day. One could say that data is nearly our native tongue. But so far we let other people, less fluent in this language, dictate which figures are important and what they tell us. So today, I start a series based on common collection issues that I can make visible using real data. I will present the figures and then analyze what they tell us.

Part 1: How bad is being a little sloppy with location tracking, really?

Recently we were improving the storage situation for some of our tin plate and enamel signs. This is just one of these situations where you stumble upon a set of very different common storage mistakes: confused numbers, wrong data base entries, missing locations… In fact, those relocation projects, following a stringent procedure of taking everything out and checking it against its data base entry are sometimes the only occasions where you have a real chance to discover objects that were marked “missing”.

Those are also projects where you sometimes encounter “time saving” ideas like “but they are all in the data base, can’t we just take them to their new location and change the location entry in the data base without cross-checking?” It’s sometimes not easy to argue against such ideas – until you have figures that tell you why it isn’t exactly a good idea. So, let’s take a look at the figures:

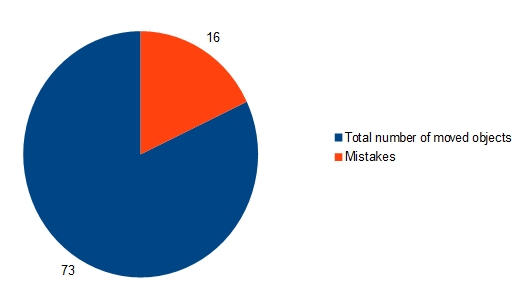

We moved 73 signs in one day. During the check we encountered the following issues:

9 signs had a wrong location in the data base. Sometimes it was an “old” location, where the sign had been before, because someone had forgotten to mark the location change in the data base or because he or she confused the accession number and made the location change for a totally different object. Sometimes the location was plain wrong because someone choose the wrong entry from the location thesaurus or, again, confused the accession number with another object.

2 signs where marked “missing” in the data base, which means that somebody already tried to find them. They were discovered when unwrapping a sign and discovering that there was a second sign packed within. One of the two had no accession number attached but could be identified later.

4 signs had a wrong accession number attached, although most of our object labels (and, in fact, all 4 labels in question here) bear pictures.

1 data base entry showed the wrong picture.

This translates into an error rate of 21,91 % which means that there was something wrong with every 5th data base entry.

Wrong location entries top the pile with 12%, followed by confused accession numbers with 5,48%, “missing” objects with 2,74% and wrong picture with 1,37%.

In the next parts of this series we will take a look at what led to these errors, how they could have been avoided and how this translates into invested working time.