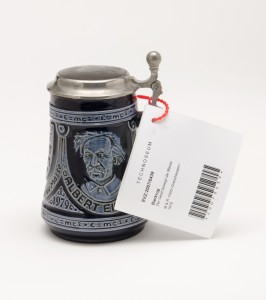

TECHNOSEUM utilizes barcodes to track collections

Barcode or RFID?

As with every practical issue, there is an abundance of technical know-how on the one hand, versus concrete local limitations on the other. Something that makes sense in one museum might not in another. At the TECHNOSEUM, we first considered several possibilities in an open and unbiased manner, starting with barcodes. Most of us know these as the striped codes on packaging in stores, or as blotchy squares of code in ads or magazines commonly known as QR codes. Next we considered RFID chips, which are usually associated with anti-theft devices or animal tracking. We also got in touch with colleagues around the world, who are already using these systems in their museums and were able to give us a great deal of insight into their problems and potential. We weighed this information against our own local conditions and decided to go with the striped barcode.

By the People, For the People

This kind of conversion has many advantages:

• Collections staff can continue working even when the scanner system is not working. People can still read all numbers and find the locations.

• Barcodes can be implemented gradually, parallel to older inventory methods, with no workflow delays when objects or locations have not been barcoded yet.

• With the low number of characters, the capacity of the classic barcode is sufficient and cheaper readers can be used.

Work on Site and in the Database

The barcode scanner works just like a keypad or mouse. When a barcode is scanned, our database (Faust 7) displays the associated record, which can then be edited. If the object’s location is to change, we scan the location barcode directly from the storage unit itself or from a list at the workstation. The barcode readers we use at the TECHNOSEUM work over a wireless network. They also have a memory function, so barcodes outside the range of the receiver can be scanned and then uploaded back at our work stations.

Implementation: From Zero to 170,000?

At first, implementing a system like this might seem like a mammoth undertaking. After all, eventually all of the TECHNOSEUM’s approximately 170,000 objects are to sport “their” barcodes. The simple directive “Everything you touch gets a barcode” makes the reality of implementing the system much less daunting. Since February 2015, every new acquisition has received its barcode as soon as it enters the collection. And every object loaned, photographed, audited, or restored gets a barcoded tag—that’s between 4,000 and 6,000 objects annually. Every object in the database already has a barcode, which automatically appears on every newly printed inventory card, packing list, and box label. Any hours our part-time student assistants have to spare are spent providing entire storage units with new inventory cards. The barcodes have withstood their first baptism by fire: the deinstallation of the “Herzblut” (Lifeblood) exhibition. About 600 of the 700 objects on display came from our own collections and were packed up and sent back to storage in June. For the first time ever, thanks to the barcodes, there were no “blind spots” in the logistics chain: every object could be found at any point in time, whether in the exhibit vitrine, the numbered packing case, or back in storage. And another first: Never in the museum’s 25-year history had an exhibition been deinstalled without a single transposed numeral—until now!

Angela Kipp

This article was originally published in KulturBetrieb, (Cultural Enterprise) a magazine for innovative and economic solutions in museums, libraries, and archives; issue 3 (August 2015). www.kulturbetrieb-magazin.de

Abbreviations and technical terms employed:

RFID (English abbreviation for “radio-frequency identification): identification using radio waves.

Translated from German into English by Cindy Opitz

I would be curious to know what you found out about RFID. Exactly what were the pros and cons? I have heard from some folks that they didn’t like it but I can never seem to get an exact answer as to why. Thank you, Sue

Hi Sue,

glad to answer that one (and it reminds me that I wanted to write a blog post on “why technology questions in museums often remind me of religious wars” but haven’t gotten to it, yet). We took a look at all available technologies and figured out what they are good at and what they are not so good at.

RFID is very powerful when it comes to track a chip or the label the chip is attached to (to attach it directly to the object was never an option for us). You can stand in a room with a scanner and it will tell you exactly if the chip you search for is in this room or not. You can narrow the range of the scanner down to a few inches and will be able to track that chip resonably exact. This ability solves a big issue in museums: you can search for objects that are “lost” and you have a ver easy inventory control.

Let’s take a look at the things RFID is not so good at: The scanners are not good at single operations. The scanner narrowed down to scan only an inch away will still display all the RFIDs it has in range. This makes it a bit cumbersome to edit a data base entry for a single object, especially in a storage with many objects.

How does it look on the material side? You have a mixture of materials, containing metal and plastics, and all RFID we researched where glued to an object or label.

What does it take to implement an RFID system? You can either order the chips from a factory or produce them yourself on specialised RFID printers.

How did these findings influence our decision making process?

When we took a look at our interaction with objects we found that the vast majority are operations with a single object. The cases where we actually wanted to search for an item in the storage where there, but it made only about 5-10% of our operations, at least in the storage. We have a very rigid location tracking, which means that most of the time IF an object has a location entry in the data base it can be found there. Most of the time we took an object out, did something with the data base entry and then put it back in its place or packed it for transport. This means that 95% of our working processes where those where RFIDs don’t have their greatest strength.

We are always trying to change non-archival materials to archival ones and the manufacturers couldn’t guarantee us that their materials are archival. In fact, none had even thought about the issue to have a material mix in a closed-up zipp-lock bag, nor where there researches on longterm stability. Together with the comparably high costs of scanners and printers RFID drpped out very early in our process. But this isn’t to say that they are not good for any other museum who has other issues than we had.

Best wishes

Angela