The damage sloppy location tracking does

I promised to take a look at the damage done by the errors recognized in the first part.

I promised to take a look at the damage done by the errors recognized in the first part.

Note: All the working time given in minutes are estimations based on real-world experiments and consider closely related working steps like, for example, that to check a rack in compact storage you need time to pull the rack out and move it back in after checking or that you have to take a sign out of a box and place it on a table when checking signs stored in a box – and that you have to put back all of them safely after checking. It does not take into account the time invested into collections improvement like cleaning, packing badly packed objects better or correcting false data base entries when you discover them while searching for that sign.

Those who believe wrong location entries don’t do a considerable damage normally have misconceptions about the museum work behind the scenes. Their reasoning goes as follows: if an object is missing, you mark it missing in the data base and carry on with your work. Their calculation is:

Going to the location stated in the data base to look for object, search for it, don’t find it there:

3 Minutes (assuming that “Every object is retrievable within three minutes”, one of the core principles of RE-ORG methodology for museum storages, see http://www.re-org.info/ for more)

Marking the object as “missing” in the data base:

1 minute

4 minutes working time wasted.

But that’s not the reality. Objects that are searched for are needed for something, may it be an exhibit or research. This means that when you can’t find it there is a whole procedure of searching taking place. How much time is wasted depends on your setting and object handling procedures. Let’s say the normal setting is that the curator searches for most of the objects he or she needs for an exhibition him- or herself. Only when he or she has trouble finding something he or she contacts the collections manager. What will happen in this setup?

The curator searches for the object at the location stated in the data base:

3 minutes

The curator searches in the direct vicinity of the location to make sure it really isn’t there and he or she hasn’t just overlooked it.

10 minutes

The curator checks the data base again to see if he or she really looked at the right location

1 minute

The curator contacts the collections manager to inform him or her about the trouble in finding the object

5 minutes

The collections manager searches the location given in the data base and its direct vicinity again to make sure the curator hasn’t overlooked something

13 minutes

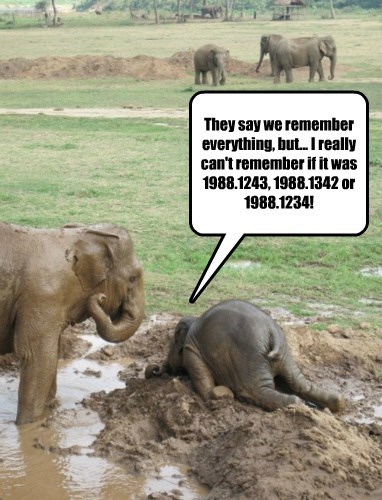

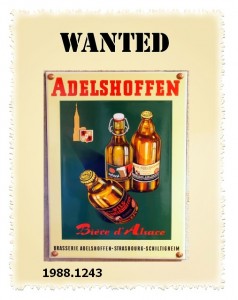

The collections manager takes a look at the object entry in the data base to see if he or she can figure out what went wrong. This means trying different combinations of confused numbers to see if it produces results that show the location of the sign. For example: if 1988.1243 and 1989.1243 are both enamel signs and 1988.1243 can’t be found at the location entered in the data base it might be found on the location that is given for 1989.1243. This might also encompass searching for previous uses of the sign to figure out if it was taken out for a loan or a conservation treatment which wasn’t noted in the data base by mistake.

30 minutes

The collections manager searches all objects of the same type to make sure the object really isn’t there. How long this takes is mainly due to the object type, storage situation and the quality of the overall museum documentation. If enamel signs are all stored in one place without exemption this is easier and quicker to check than if they can be found at various storage locations. If all enamel signs hang open and visible in compact storage they are easier to search than if they are all wrapped in bubble wrap. If they hang wrapped they are easier to search than if they are crammed into open shelving or boxes. If the bubble wrap has a printed out picture of the sign on it it is easier to search than if the wrap only carries the number.

Well, we have about 750 enamel signs. Let’s say we can narrow this sample down to 200 if we take the size as quick criteria what signs we have to check and which we don’t have to check. Here is the time it takes to check in all already discussed scenarios:

Compact storage (assuming that one rack holds 20 signs that are hung open or are wrapped but have a big printed picture in front and that you have a picture of the sign you search for):

4 minutes per rack = 40 minutes

Compact storage (assuming that one rack holds 20 signs that are wrapped and clearly signed with the accession number):

7 minutes per rack = 70 minutes

Open shelving or boxes (assuming that one shelf or box holds 10 signs):

15 minutes per shelf = 300 minutes

It’s astounding to see the increase of working time that comes with not ideal storage conditions. The time given for storage in boxes or open shelving in this scenario is still kind of ideal: the working time invested increases even more if boxes have to be moved with a pallet truck or a forklift, if the signs are not all stored in one place and if location entries are vague. Of course, sometimes you won’t have to search through all the 200 signs to find the right one. On the other hand, Murphy’s Law is still in place, so it might well be that the sign you search for is the last sign that you check. And: signs are rather easy to search for, compared to a missing coffee maker in a collection of 200 coffee makers in 18 shelving units, presumably all wrapped in nice bubble wrap and just labeled with accession numbers. Still a doable task, assuming that all coffee makers are stored together. It becomes “mission impossible” if every single nicely wrapped package in 400 storage units could hold the missing item.

Well, back to our figures…

The collections manager is changing the location entry if he or she has found the object or marks it as “missing” in the data base:

1 minute

The collections manager informs the curator if the object was found or if it is missing

5 minutes

In the worst case the object can’t be retrieved despite all efforts and this leads to even more invested working time by the curator who has to search for a replacement. Along with the increased research time this might even result in additional costs like shipping fees if he or she needs to borrow the replacement from another institution or traveling costs if he or she has to travel to another institution for research. But let’s just take stock here:

Invested working time curator (the information exchange between curator and collections manager is counted for both):

24 minutes

Invested working time collections manger in a perfectly organized collections setup:

94 minutes

Invested working time in a standard collections setup:

124 minutes

Invested working time in a sub-standard collections setup:

354 minutes

This means that even in a well-managed setup a wrong location entry leads to about 2 hours of invested staff time.

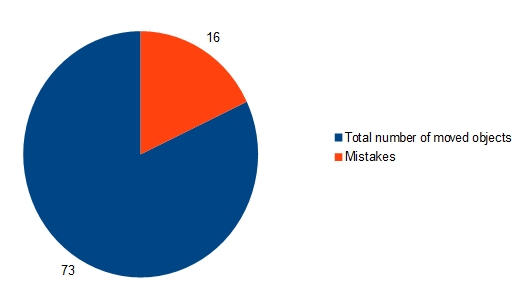

Which brings us to the question how often this happens. Upper management will normally assume that this is the exception, not the rule. They reason that their collections managers are detail-oriented and dedicated staffers who will have their collection well organized so these failures are certainly not very common. On the other hand, many collections managers will probably tell you “it happens EVERY time!” So, which assumption is right? Well, they are both right and both wrong. If we take a look at the figures from our first part we got an error rate of 21,91 %. As we only look for objects that were not found on their location we can neglect the “wrong picture” case (although this could make the retrieval process more complicated) so our error rate becomes 20,54 %. If we assume for a moment that this percentage is common in other collections, too, this means that there is something wrong with the location entry of every fifth object. In other words: if you get a list of 15 objects to retrieve you will have difficulties with finding 3 of them. Of course, this isn’t inevitably so, but it explains why many collections managers think of it as something that happens EVERY time as it possibly happens with at least one object in every task they get on their desk.

So, are most collections managers not as detail-oriented and dedicated as upper management thinks? Is our self-perception that we are of course detail-oriented, sometimes in an obsessive-compulsive way, so completely wrong? Are we really that sloppy? Or are there reasons other than carelessness responsible for the figures we just saw? We’ll take a look at that in the next part of our series.

This may seem a weird way to start an article written for registrars, but many years ago, I attended a day of clown school. It was a pretty unique experience, and (little did I know at the time) it was also an experience would turn out to have something in common with working as a registrar! Be you clown or registrar, the art of juggling is an important part of the job. For a registrar working with loans, for example, juggling is required to ensure that the demands of both the lender and their institution are satisfied to a standard that will enable the loan to proceed. When it comes to university museums, however, there is a whole extra level of complexity to these loan negotiations. University museums commonly undertake intra-institutional loans to all sorts of locations around their own university. Your items may still be ‘on-site’, but how much influence can you actually maintain over your loans in these circumstances? Juggling balls can all too quickly become chainsaws when you realise that there are many competing demands to manage in this environment, some of which are out of your control. The requirements of collections care and preservation, for example, can struggle to make themselves heard against the demands of institutional expectations, history and politics. Where do you draw the line on loan requirements in these circumstances? Is there, in fact, a line? Or is it a tightrope, perhaps? This was the very interesting subject which formed the basis for a fascinating session on the morning of Day 2 of the 2015 ARCS Conference in New Orleans.

This may seem a weird way to start an article written for registrars, but many years ago, I attended a day of clown school. It was a pretty unique experience, and (little did I know at the time) it was also an experience would turn out to have something in common with working as a registrar! Be you clown or registrar, the art of juggling is an important part of the job. For a registrar working with loans, for example, juggling is required to ensure that the demands of both the lender and their institution are satisfied to a standard that will enable the loan to proceed. When it comes to university museums, however, there is a whole extra level of complexity to these loan negotiations. University museums commonly undertake intra-institutional loans to all sorts of locations around their own university. Your items may still be ‘on-site’, but how much influence can you actually maintain over your loans in these circumstances? Juggling balls can all too quickly become chainsaws when you realise that there are many competing demands to manage in this environment, some of which are out of your control. The requirements of collections care and preservation, for example, can struggle to make themselves heard against the demands of institutional expectations, history and politics. Where do you draw the line on loan requirements in these circumstances? Is there, in fact, a line? Or is it a tightrope, perhaps? This was the very interesting subject which formed the basis for a fascinating session on the morning of Day 2 of the 2015 ARCS Conference in New Orleans.